Norvin Richards remembers the first time he heard the Wolastoqey language spoken — and how much he has smiled over the years in the company of those who have helped him learn it.

The linguistics professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was at a conference in Connecticut 15 years ago when he met elder and language-keeper Imelda Perley and now-friend and fellow linguist Roger Paul.

“If you’ve heard it spoken, you know it has this beautiful sort of singsong cadence to it that made me, as a linguist, think, ‘Oh, I would really love to learn to speak that way,'” Richards said. “It’s just such a gorgeous language.”

He and Paul are part of a larger effort to save the Wolastoqey language which, according to Statistics Canada, has only about 750 remaining speakers.

Elders pass on language, and a nickname

Richards said the language drew him in, but it was getting to know fluent speakers like Paul and his uncle, the late Raymond Nicholas of Neqotkuk, that hooked him.

“It’s a culture that traditionally … it seems to place a big value on being good at talking, on being a storyteller, on being a joker,” Richards said. “And so when these people get together, they just have a wonderful time talking, and it’s wonderful to be around.”

Richards spent a sabbatical in northeastern New Brunswick, learning Wolastoqey from “Uncle Raymond” and Imelda Perley, recording traditional stories and trying to understand the rules of the language.

Paul, said elders give nicknames to their “favourite linguists that come around,” and Richards is one of them.

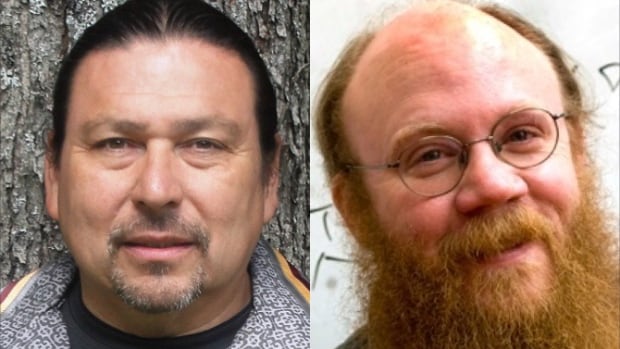

His nickname is Mehqituwat, which means “has a red beard,” said Paul, who studied with Richards at MIT and now teaches at the University of Southern Maine.

“Normally, the word ‘linguist’ in a community raises the ire of a lot of people because we’ve had the wrong type of linguist come around before and tell us that we didn’t know enough of our own history,” Paul said.

“But when you have linguists like Mehqituwat come in and they are just wonderful people and fit right into our communities … we kind of adopt them and give them our pet names.”

Richards is now heading into another sabbatical and has set a goal of becoming a fluent Wolastoqey speaker by the end of it.

Paul said his friend already “communicates very well,” and is close to fluency.

“He even lies well in Wolastoqey,” he joked.

‘It’s not too late’

Richards and Paul know the Wolastoqey language is threatened, and both attended a language conference in Fredericton this fall that focused on reclamation.

“I left feeling better than I’ve ever felt before because I watched the presentations of the young people,” Paul said.

Richards agreed that it is the young speakers who will determine the survival of the language.

He knows from his work with the Wampanoag in Massachusetts, relatives of the Wolastoqey, how difficult it is to try to revive a language that is extinct.

“They have no speakers at all,” he said. “But we have many documents, including a complete translation of the Bible and a lot of religious literature and a lot of documents written by native speakers. The Wampanoag are very interested in sort of piecing their language back together from those documents.”

In comparison, with 750 speakers the Wolastoqey are way ahead of reclaiming and revitalizing their language.

“It is wonderful to be here surrounded by these elders and sort of to be reminded that this language is still going on, that there are still fluent speakers, that it’s not too late,” Richards said.

‘Uncle Raymond’ was right

Paul said that when he was young, he didn’t appreciate the importance of growing up in a proud Indigenous family that refused to speak English and only spoke to him in Wolastoqey.

He didn’t hear English until the age of five or six, he said, when he “went to the day school for a little bit.”

“I didn’t start speaking until Sister Jean-Marie started teaching me English.”

Paul remembers going every Saturday to his Uncle Raymond’s house in Neqotkuk or Tobique, where elders would gather and teach him words in Wolastoqey.

“I’d have to sit there and get drilled by the elders and told what I need to learn and what I need to teach.”

At the time, he was “just a young buck, not even knowing where my tail was half the time,” Paul said, remembering how he would roll his eyes at the elders.

Now as a linguist and a lecturer at the University of Southern Maine, he wishes he could remember all of what they taught him.

“Uncle Raymond had a word for what bushes looked like after moose had just run through them. And I promised him I’d remember that. But rest his soul, I don’t remember that one.”

Paul doesn’t believe the latest census numbers that show there are 750 Wolastoqey speakers, saying he thinks it’s more like 200 or 300, but he does believe his language will survive.

“I remember my uncle saying — he told me in the language, ‘Someday you’re going to be thankful I taught you this boy.'”

Now that he is a language teacher, Paul understands the importance of what Uncle Raymond was telling him.

“Every day I get up to come to work I hear those words in my ear,” he said, laughing. “Yeah, OK, you were right.”