Mythology has its titans. So do the movies. And so does physics. Just one fewer now.

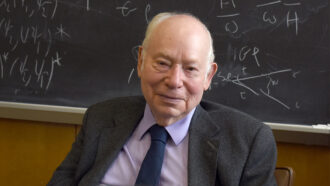

Steven Weinberg died July 23, at the age of 88. He was one of the key intellectual leaders in physics during the second half of the 20th century, and he remained a leading voice and active contributor and teacher through the first two decades of the 21st.

On lists of the greats of his era he was always mentioned along with Richard Feynman, Murray Gell-Mann and … well, just Feynman and Gell-Mann.

Among his peers, Weinberg was one of the most respected figures in all of physics or perhaps all of science. He exuded intelligence and dignity. As news of his death spread through Twitter, other physicists expressed their remorse at the loss: “One of the most accomplished scientists of our age,” one commented, “a particularly eloquent spokesman for the scientific worldview.” And another: “One of the best physicists we had, one of the best thinkers of any variety.”

Weinberg’s Nobel Prize, awarded in 1979, was for his role in developing a theory unifying electromagnetism and the weak nuclear force. That was an essential contribution to what became known as the standard model of physics, a masterpiece of explanation for phenomena rooted in the math describing subatomic particles and forces. It’s so successful at explaining experimental results that physicists have long pursued every opportunity to find the slightest deviation, in hopes of identifying “new” physics that further deepens human understanding of nature.

Weinberg did important technical work in other realms of physics as well, and wrote several authoritative textbooks on such topics as general relativity and cosmology and quantum field theory. He was an early advocate of superstring theory as a promising path in the continuing quest to complete the standard model by unifying it with general relativity, Einstein’s theory of gravity.

Early on Weinberg also realized a desire to communicate more broadly. His popular book The First Three Minutes, published in 1977, introduced a generation of physicists and physics fans to the Big Bang–birth of the universe and the fundamental science underlying that metaphor. Later he wrote deeply insightful examinations of the nature of science and its intersection with society. And he was a longtime contributor of thoughtful essays in such venues as the New York Review of Books.

In his 1992 book Dreams of a Final Theory, Weinberg expressed his belief that physics was on the verge of finding the true fundamental explanation of reality, the “final theory” that would unify all of physics. Progress toward that goal seemed to be impeded by the apparent incompatibility of general relativity with quantum mechanics, the math underlying the standard model. But in a 1997 interview, Weinberg averred that the difficulty of combining relativity and quantum physics in a mathematically consistent way was an important clue. “When you put the two together, you find that there really isn’t that much free play in the laws of nature,” he said. “That’s been an enormous help to us because it’s a guide to what kind of theories might possibly work.”

Attempting to bridge the relativity-quantum gap, he believed, “pushed us a tremendous step forward toward being able to develop realistic theories of nature on the basis of just mathematical calculations and pure thought.”

Experiment had to come into play, of course, to verify the validity of the mathematical insights. But the standard model worked so well that finding deviations implied by new physics required more powerful experimental technology than physicists possessed. “We have to get to a whole new level of experimental competence before we can do experiments that reveal the truth beneath the standard model, and this is taking a long, long time,” he said. “I really think that physics in the style in which it’s being done … is going to eventually reach a final theory, but probably not while I’m around and very likely not while you’re around.”

He was right that he would not be around to see the final theory. And perhaps, as he sometimes acknowledged, nobody ever will. Perhaps it’s not experimental power that is lacking, but rather intellectual power. “Humans may not be smart enough to understand the really fundamental laws of physics,” he wrote in his 2015 book To Explain the World, a history of science up to the time of Newton.

Weinberg studied the history of science thoroughly, wrote books and taught courses on it. To Explain the World was explicitly aimed at assessing ancient and medieval science in light of modern knowledge. For that he incurred the criticism of historians and others who claimed he did not understand the purpose of history, which is to understand the human endeavors of an era on its own terms, not with anachronistic hindsight.

But Weinberg understood the viewpoint of the historians perfectly well. He just didn’t like it. For Weinberg, the story of science that was meaningful to people today was how the early stumblings toward understanding nature evolved into a surefire system for finding correct explanations. And that took many centuries. Without the perspective of where we are now, he believed, and an appreciation of the lessons we have learned, the story of how we got here “has no point.”

Future science historians will perhaps insist on assessing Weinberg’s own work in light of the standards of his times. But even if viewed in light of future knowledge, there’s no doubt that Weinberg’s achievements will remain in the realm of the Herculean. Or the titanic.