As It Happens6:10Homosexuality used to be classified as a mental illness. This man helped change that

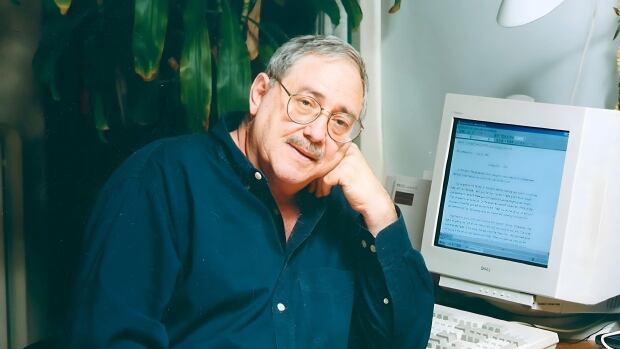

Dr. Charles Silverstein accomplished a lot in his life.

As a psychologist, he used his clinical practice to help LGBTQ patients embrace their identities at a time when conversion therapy was the norm.

He authored several books, including For The Ferryman, his 2022 memoir published by ReQueered Tales, and The Joy of Gay Sex, an explicit and illustrated guide to sex, which he co-wrote with Edmund White. The latter, which has spawned several updated editions, was controversial when it came out. It was repeatedly seized, burned, hidden from bookshelves, and outright banned.

But perhaps his greatest feat was his speech to the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 1973, in which he, along with other panellists, argued that homosexuality should not be considered a mental illness.

Ten weeks later, the APA removed homosexuality from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a guidebook used in the U.S. and Canada to diagnose mental illness.

Silverstein died on Jan. 30 at his New York home from lung cancer, the Washington Post reports. He was 87.

Dr. Barabara Kapetanakes, his friend and colleague, spoke As It Happens host Nil Köksal. Here is part of their conversation.

I want to talk about Mr. Silverstein’s professional accomplishments, of course. But I also wanted to ask you what kind of friend he was to you.

Even though he had accomplished so much, and even though he was ahead of the curve on LGBT rights and part of the movement very, very early on, he really didn’t have a lot of ego about it.

He was just a regular guy who just wanted to see his friends and cook delicious dinners and bring bagels to meetings.

Do you think younger generations in the community know him well enough?

I don’t know…. Recently, there had been two documentaries out in maybe the last four or five years that looked at different aspects of the gay rights movement, and he was in them. I certainly shared them with classes that I’ve taught so that young people would see these people who did the work 50 years ago.

I think in a lot of the movements, young people don’t realize how recent it is and how tenuous some of the rights that were won actually are.

Did it matter to him, or was he just happy that he had been able to effect some change?

I think he was concerned … that once rights are secured, people think that they’re secured forever.

So I think that he was happy as long as people continued to fight the fight. It didn’t matter if they did it in his name, or because of him, or if they did them for any other reason, as long as they continued to move forward.

It was February of 1973 when he spoke to a committee of the American Psychiatric Association and addressed this issue of declassifying homosexuality as a mental disorder. But his approach was unique and clearly got the point across. Can you just tell me about what he said?

What he did was he looked at all the other things that we have seen as disorders throughout the years.

When I teach general psychology and teach about the history, one of the ones I find very comical is that they believed that women became hysterical because the uterus had broken free and was running through the body, and you had to lure the uterus back to its place.

And he kind of tried to make that same point of: Look at some of the things that we have called illnesses in the past. Look at some of the treatments we have used in the past. We look at it now and we think that that’s crazy. Well, why do we still think that homosexuality is a disorder? That this is going to look crazy to us in 50 or 100 years as well.

How do you assess the lasting impact of that victory for the community?

I think that it gave people permission to be who they were. Because … aversion therapy, trying to change people’s sexual orientation, it doesn’t work.

So I think [it allowed] people to say, “Well, this is who I am and it’s OK to be who I am. I’m not depressed because I’m a gay man or I’m a lesbian. I’m depressed because you’re repressing me and you’re treating me in these ways.”

He wrote The Joy of Gay Sex, talking about gay men, in particular. It was censored heavily in Canada, as I understand it. That was the next step in helping the community for him, right? How did that help — that kind of openness and the words and the experiences, sharing that so openly?

Charles himself said that when he first started being sexually active with men, he didn’t know what he was doing. There was no book, and everything was secret. Everything was private. Everything was shameful.

His hope was — and I think he succeeded in many ways — that the book would allow a younger generation to read the book and understand that you can have sex with another man, you can be in love with another man, you can have a partnership with another man, and that this wasn’t shameful, and we can talk about it, and you can have your questions answered.

I think that was huge for him. And I know that it was edited a couple of times, like when the AIDS crisis hit. It was edited to reflect that crisis, and safe sex and the reality of what was going on in the community.

What did he make of where things are at right now?

I know one of his concerns was with the overturning of things. Like, even the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Does that set a precedent to overturn other previously decided decisions? Things that we thought were decided and not to be overturned? So gay marriage, interracial marriage, sodomy laws?

I think that his biggest concern was that all of this progress had been made over 40 or 50 years, and that the holds that some particular groups have on politics, is causing some of these things to be overturned or to be in jeopardy.

What is the memory or the image of Charles that you will hold the closest to in your memory?

He tended to walk around in like a plaid flannel shirt, you know, looking like a lumberjack kind of. Or if you were on Zoom, he might be in a smoking jacket or a kimono.

And that was kind of Charles. You never knew what you were going to get, and everything was always with a wink.

I did see him just a few weeks before he died. I brought lunch over to his apartment. He had this beautiful, huge Upper West Side apartment [in New York City] filled with artwork, filled with things from [when] he travelled around the world and brought home all kinds of artwork and souvenirs from his travels. The place was just floor to ceiling full of these great things.

He wasn’t cooking anymore because he was … not well, but he used to love to make big dinners. But I brought some food over from one of his favourite restaurants and was just able to sit with him and just kind of hang out.

He wanted to say goodbye to his friends.