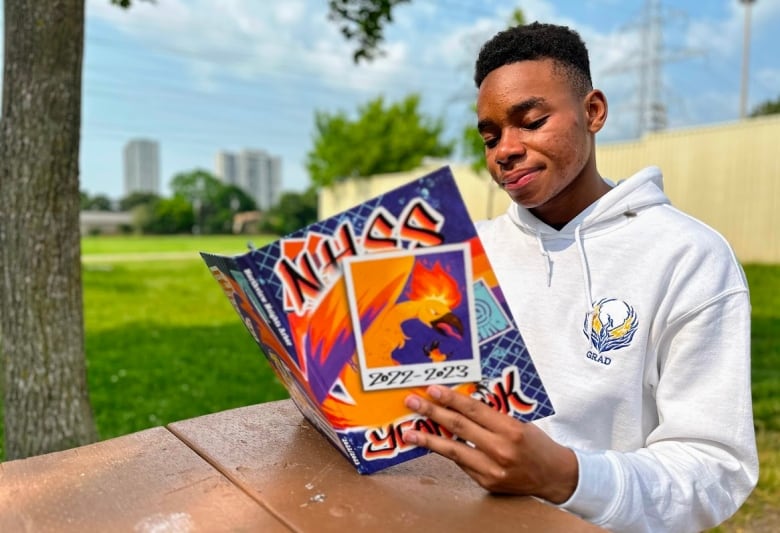

Tyson Hamilton has a 96 per cent average and was president of his high school student council, but the Grade 12 student did not get admitted into business degree programs at the University of Toronto, Queen’s or McMaster.

While Hamilton received offers from seven other university programs and is excited about his choice to enrol in a dual degree program at Western University this fall, he wonders why programs would reject an A-plus student.

“If a 96 isn’t good enough, what is?” said Hamilton in an interview. “Where does it stop? Is everyone going to be needing 100 averages to get into these programs?”

His rejections are the result of a trend that reveals an increasingly larger number of students with high grades competing for Ontario’s most coveted post-secondary spots.

The average Grade 12 marks of students enrolling in first-year programs at Ontario universities have been rising steadily upward, according to data compiled by the Council of Ontario Universities.

The data also shows growing proportions of students entering university after obtaining Grade 12 averages in the 95-plus and 90 to 94 ranges.

The trend is particularly apparent in the highly competitive university programs of business, engineering and biological sciences, but is also evident among students choosing social sciences and liberal arts.

Are you a high-achieving Grade 12 student who was rejected by some Ontario universities? Send an email to CBC News to tell us your story.

“I think the issue is right now, there’s no [marking] consistency across schools.” he said. “A 96 at one school might be worth a low 90 at another school.”

The data raises questions about why the marks are rising and what it means for students trying to gain admission into Ontario’s most competitive university programs. The answers are complex and nuanced.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the grades of Ontario high school students had increased gradually but steadily for years. It’s a trend that has accelerated since 2020.

“In the pre-COVID years, there’s reason to think it might actually reflect higher achievement,” said Kelly Gallagher-Mackay, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University who studies educational inequality.

Gallagher-Mackay attributes the rising grades to a combination of effort within Ontario’s school system to improve equity of outcomes, moves to end streaming of students into applied courses, and shifts in immigration that brought more families who prioritized academic achievement.

The jump in marks since the pandemic began, however, is so dramatic that it can likely only be explained by additional factors.

Toronto District School Board data shows the average Grade 12 student’s mark rose from 71 to 77 in a two-year period after the pandemic began.

“That’s huge and pretty unprecedented,” said Gallagher-Mackay. The previous six-point rise took 13 years.

The data appears in a report by Gallagher-Mackay and York University adjunct professor Robert Brown, published by the Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Why grades spiked since COVID

Further research by the pair — using data from six large school boards that represent one-third of Ontario’s student population — found that the proportion of Grade 9 students with 90-plus averages rose from 12 per cent in the 2018-19 school year to 23 per cent in 2020-21.

Much of that rise occurred in the spring of 2020, when Ontario’s Ministry of Education issued a directive that each student’s mark in each course must not fall below where it stood when the pandemic forced the cancellation of in-person classes.

The increase continued in the tumultuous 2020-21 school year, when many Ontario school boards shifted back and forth between in-person and remote learning.

Gallagher-Mackay attributes that increase in part to teachers shifting their methods of assessing achievement, giving students greater opportunities to demonstrate what they’d learned, with decreased emphasis on exams. She says teachers may also have used marks as a way to motivate and encourage students through the challenges of remote learning.

“I think the teachers’ strategy was to try and give students some hope and optimism, and arguably, I think it worked for most students,” she said. “If it really stressed out the parents of kids who before would have had a 94 and now are fighting for a 97, that might have been an OK cost.”

For universities, the ballooning numbers of high-achieving high schoolers can make it challenging to decide which students to admit to competitive programs.

Dwayne Benjamin, the University of Toronto’s vice provost of strategic enrolment management, says grade inflation also creates challenges for incoming students.

“They may have an exaggerated sense of their own preparedness,” said Benjamin.

“Grades are information. Grade inflation distorts the information and degrades the quality of the information,” he said. “To the extent that the grades don’t mean the same thing one year to the next, it makes it difficult for everybody.”

Universities rely largely on the relative ranking of students provided by grades (rather than the numbers themselves) to predict which students are most likely to succeed, said Benjamin.

“Typically it’s going to be the case, if you have a five per cent higher grade than your classmate in your high school, you’re more likely to get into the program,” said Benjamin. “But if you have a five per cent higher average than a kid at another high school, that isn’t necessarily going to make the difference.”

‘A stab in the heart’

Jeffrey Osaro, a Grade 12 student at Northview Heights Secondary School in Toronto, had a 92 average when applying for university programs this spring. He was rejected by the bachelor of commerce programs at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, Queen’s University’s Smith School of Business and Western’s Ivey Business School.

Not getting into Ivey “was just a stab in the heart,” said Osaro in an interview. “I had my heart set on going to Ivey.”

Osaro said a lot of people around him had given him high hopes of getting into the program.

“Obviously there are [other] students who have accelerated, high-achieving grades,” he said. “I can’t compare to that, but I do believe I was a well-rounded student.”

He’s a student trustee of the Toronto District School Board, volunteered with a program teaching hockey to kids from low-income communities, served as a homework tutor at the Salvation Army and was president of Northview’s student council. He accepted an offer from Western’s bachelor of management and organizational studies program.

While a student’s six best marks in Grade 12 university-level courses are the standard benchmark, not all Ontario university programs make admissions decisions based solely on that figure.

Some programs give greater weight to a student’s mark in certain courses, and highly competitive programs ask for supplementary information, including resumes and written statements.

The dynamics of supply and demand for spots in certain programs have had more impact on pushing averages upward than grade inflation, says Andre Jardin, the University of Waterloo’s associate registrar of undergraduate admissions.

“We have a lot of applications from a lot of fantastic students, so that tends to be what increases our admission averages,” said Jardin. “Essentially you have to be the top student to even be applying to these programs to have a realistic chance at getting in.”

The University of Toronto has not seen any significant drop in the retention rate of students successfully moving on from first to second year amid the rising grades, says Benjamin. Still, he says faculty are reporting that incoming students seem to be struggling more than in the past, a factor likely attributable to the pandemic’s disruption of their high school lives.

“High school grades get you in the door, but you’re going to have to really prove yourself in first year, which is more challenging for some than others,” he said.

Many high school students want to know what marks they need to get accepted into selective university programs. But the data provided by Ontario’s universities related to admissions aren’t expressed as cut-off grades for entrance.

Instead, each university provides an overall average of the Grade 12 marks for students who enrolled in each program, and the proportion of enrolled students whose marks fell within five-point ranges (95 and up, 90 to 94, 85 to 89 etc.).

A few examples from the data:

-

At McMaster University, 50.4 per cent of students who enrolled in all first-year programs in 2017 had a Grade 12 average mark of 90 or higher. By 2020, that proportion rose to 63.9 per cent.

-

At the University of Toronto, 52.5 per cent of students who enrolled in the first-year engineering program in 2017 had a Grade 12 average of 95 or higher. By 2020, that had risen to 68.4 per cent.

-

At Queen’s University, 31.5 per cent of students who enrolled in the first-year bachelor of commerce program in 2017 had a Grade 12 average of 95 or higher. By 2020, that had risen to 43.5 per cent.