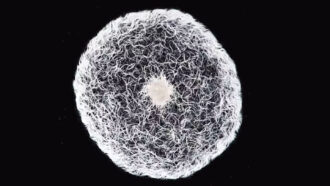

Trapped within a bead of water, thousands of tiny worms wiggle in hypnotic synchrony as they stream around the globule’s rim. And at the center of this undulating gyre some of the creatures congregate into a writhing mass, like the pupil of a demonic eye.

These squiggling creatures are Turbatrix aceti, a species of nematode commonly known as vinegar eels. Individual vinegar eels are often found swimming freely in jars of raw vinegar or in fish tanks. But when troupes of them assemble, vinegar eels showcase a unique juggling act of behaviors; they can wiggle in synch as they move together in swarms, researchers report January 10 in Soft Matter.

This captivating ability is exceedingly rare in nature. Birds and fish can move collectively, while some bacteria can coordinate the waving of whiplike appendages (SN: 7/31/14; SN: 5/28/19; SN: 7/13/15). Vinegar eels, however, are capable of more. “This is a combination of two different kinds of synchronization,” says Anton Peshkov, a physicist at the University of Rochester in New York. “Motion and oscillation.”

Peshkov and his colleagues first heard rumors of vinegar eels’ weird motions while studying the group movements of brine shrimp, another common aquarium dweller. Intrigued, they packed thousands of T. aceti into droplets to observe under a microscope.

The nematodes first roamed randomly, but over the course of an hour, some began clustering in the middle. Others swarmed to the edges, where they circled the rim. After a while, individual nematodes started oscillating in synch, and the swarm itself began undulating, like fans doing the wave at a sports game.

These collective undulations stirred up flows that prevented the water drop’s edge from contracting as it evaporated. But as evaporation progressed, the edge instead gradually tilted inwards, weakening the swarm’s outward push, until the walls finally began to close in. At this tipping point, the researchers measured the drop’s dimensions, which let them estimate that each vinegar eel generated 1 micronewton of force. They could move objects hundreds of times their own weight, Peshkov says.

It remains unclear why vinegar eels exhibit this bizarre behavior. “Nematodes are too small to observe in their natural environment,” says Serena Ding, a biologist at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior in Konstanz, Germany, who was not involved in the study. Figuring out the natural cause for this behavior is difficult using lab observations, since captive creatures act differently, she says.

Peshkov speculates vinegar eels might swarm tightly to minimize their bodies’ exposure to corrosive free radicals in water, or maybe they generate flows to move nutrients.

Regardless, Ding says, “this is cool.”