Every Olympics has its twists and turns leading up to the opening ceremony.

It has been an exceptionally tumultuous ride for Tokyo 2020, however, as organizers grappled with numerous scandals, including ballooning expenses, accusations of plagiarism and bribery as well as high-profile gaffes, topped off by a once-in-a-century global pandemic forcing an unprecedented one-year postponement of the games.

While it’s unclear whether the years of preparation that went into realizing the sporting extravaganza will pay off, it seems likely that with no overseas spectators and the nation in the midst of a mass inoculation drive, it will be an event unlike any seen in the history of the quadrennial competition.

“Japan got the short end of the stick in terms of being hit by a pandemic, but I think that also laid bare the numerous issues facing the Olympics and its organizers,” says Kazuya Yamazaki, an architect and specially appointed professor at the Shibaura Institute of Technology.

Public opinion remains divided over the wisdom of going ahead with the Olympics and Paralympics when a little more than 10% of the population has been fully vaccinated as of the end of June. Health experts warn that the games could trigger a superspreader event in Tokyo, while the capital’s sweltering summer heat could pose a serious risk to athletes.

“After all this, I doubt Japan would want to be hosting another Olympics anytime soon,” says Yamazaki, who worked on several projects for the 2012 London Olympics when he was employed by British firm Allies and Morrison. He has been closely following the construction of Tokyo’s competition facilities — the most prominent being the new national stadium that was at the center of controversy during its inception.

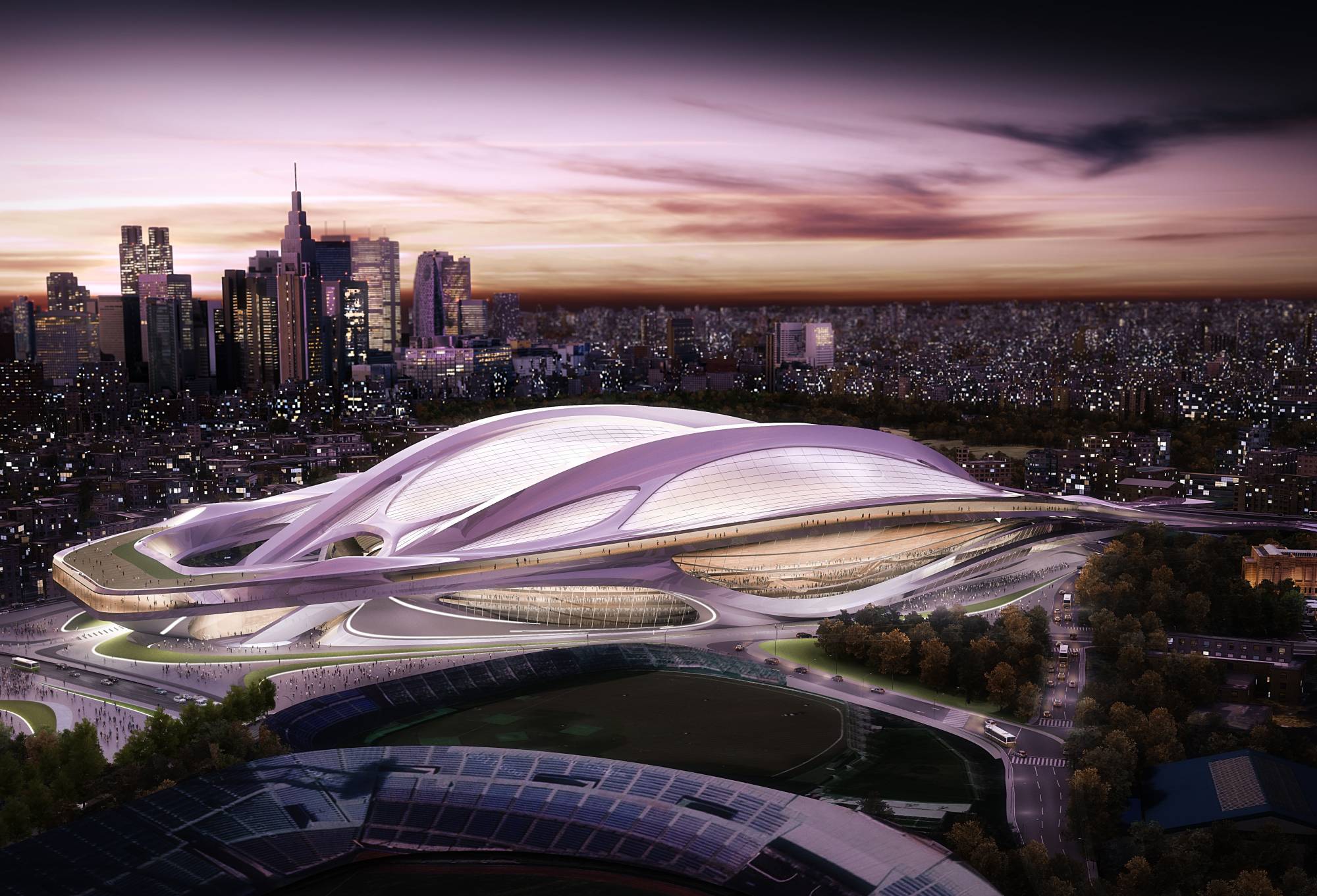

The original plan for the new sporting venue was designed by Iraq-born, U.K.-based architect Zaha Hadid, who later modified the concept after public outcry over its enormous size and price tag. But with estimated costs still running to the tune of ¥252 billion — almost double the original budget and making it the most expensive stadium of modern times — the plans were scrapped in July 2015 by then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

After a rebid, architect Kengo Kuma was chosen to design the new stadium. It was completed in late 2019 at the site where the old stadium that served as the main venue for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics stood.

“Organizers had to quickly reach a point of compromise. It may not be Mr. Kuma’s most ambitious design or fully reflective of his creative vision, but he did what he had to in the limited amount of time,” Yamazaki says. More of an issue, perhaps, is the post-games promotion of the ¥157 billion, 68,000-seat stadium and other Olympics sites, he says.

According to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, five out of the six new venues owned by the capital are expected to run annual deficits after the games. Meanwhile, the Japan Olympics Committee intends to sell the rights to operate the new national stadium after the games, but with annual maintenance fees costing around ¥2.4 billion, finding a buyer may prove challenging.

“I don’t think organizers put much thought into the legacy of the Olympics,” Yamazaki says.

Preparation for the games was dealt another humiliating blow just two months after Hadid’s design was ditched, when the Tokyo 2020 Olympic emblem was scrapped over plagiarism allegations surrounding the designer Kenjiro Sano.

The design came under fire after being unveiled in July 2015 for its similarity to the logo for Theatre de Liege in Belgium. While Sano denied the allegations, netizens soon raised suspicions that other images that Sano’s office used, including those for a Suntory promotion campaign, closely resembled pre-existing designs.

On Sept. 1, the organizing committee said it would be scrapping the emblem and launching a competition to design a new logo. The committee, however, said it didn’t decide to pull the design because it believed Sano was guilty of wrongdoing. Rather, “we thought it might be difficult to get support from the general public” given the size of the issue, according to Toshiro Muto, director general of the committee.

“The plagiarism scandal raises several interesting observations,” says Nobuhide Otomo, a professor at Kanazawa University and an expert on intellectual property. “Both Sano and the organizing committee never admitted that the Olympic logo was plagiarized. The lawyers hired by the committee also didn’t show up to any of the related news conferences, implying that they may have been determined not to turn this into a legal issue that could pin them in a corner.”

The incident also highlighted the power of the internet and how individuals with time and the right search tools can launch online investigations into anyone with digitally traceable records.

“Most firms protect their trademarks to distinguish themselves in their particular industry or market, but with so many sponsors supporting the games, the Olympic logo faces much wider scrutiny,” Otomo says. “It comes down to how the amateur ideals of the Olympics have been overrun by commercialization. It’s all about sponsorships, advertisements and marketing now.”

Soon after the plagiarism ruckus, another scandal emerged in early 2016 when French prosecutors said they were inspecting more than ¥200 million in payments allegedly made by the Tokyo Olympic bidding team to a consulting firm in Singapore immediately before and after the capital’s victory in September 2013.

JOC President Tsunekazu Takeda subsequently said he did nothing wrong in his role as head of the bidding committee. The JOC’s own probe into the matter, which wrapped up in September that year, concluded that the bidding committee’s contract with the consulting firm was executed under legitimate internal processes. However, Takeda wasn’t let off the hook that easily.

The allegations resurfaced three years later.

In January 2019, Takeda confirmed during a news conference that he had been questioned and placed under formal investigation by French authorities the previous month. The case centered on suspicion that part of the payment made to the consultancy landed in the pocket of disgraced former world athletics chief Lamine Diack, who was an International Olympic Committee member at the time of Tokyo’s bidding, with perceived influence over African voters.

In March, Takeda announced his resignation as president of the JOC and head of the IOC’s marketing commission. He insisted that he didn’t do anything illegal or wrong, however, and said he was stepping down to “make room” for the younger generation.

While Takeda was getting heat from French investigators, a different kind of heat would soon find Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike at odds with the IOC.

In October 2019, the IOC announced, to the dismay of Koike, that it was considering moving the men’s and women’s marathons, 20-km walks and the men’s 50-km race walk to Sapporo, the prefectural capital of the northern island of Hokkaido. The marathons, which were slated for August, were originally scheduled to start at 7:30 a.m. Organizers then moved up the times twice — to 7 a.m. and then 6 a.m. — due to concerns about the capital’s notoriously hot and humid summers.

Koike eventually agreed to the relocation, which her political party estimated would cost more than ¥34 billion.

“I considered putting up more of a fight but the chances of winning were slim,” the governor said.

Despite the hiccups, preparations appeared to be going as planned for the summer Olympics and Paralympics at the beginning of last year. The new Olympic logo could be seen everywhere — on promotional posters, subway ads and on television commercials sponsors aired. This was Tokyo’s chance to emulate its success at the 1964 Olympics and shine at the center of the world stage.

Then the pandemic hit.

The first case in Japan was confirmed on Jan. 16, 2020. A Chinese national living in Kanagawa Prefecture tested positive after returning from Wuhan, China. The reported number of infections gradually rose and, in March, Abe and IOC President Thomas Bach agreed to postpone the games for a year for the first time in the history of the modern Olympics. Case counts kept on growing, and the nation’s first state of emergency was subsequently announced on April 7, with two further declarations having been announced since.

In August last year, Abe said he would be stepping down due to health issues. His chief cabinet secretary, Yoshihide Suga, became prime minister the following month.

Meanwhile, organizers scrambled to contain the fallout from offending comments made by gaffe-prone former Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori, chief of the Tokyo 2020 organizing committee.

In February this year, the octogenarian triggered an uproar both at home and abroad when he said women talk too much, causing meetings to drag on. Olympic sponsors, including Toyota Motor Corp., expressed disappointment, while hundreds of Olympic volunteers backed out from the games.

While Mori apologized and retracted his comments, he resigned later that month. He wasn’t the only high-profile Olympics executive who quit over sexist remarks, however.

In March, the creative director of the Olympics, Hiroshi Sasaki, also stepped down after the weekly tabloid Shukan Bunshun revealed that he had privately suggested having plus-sized comedian and celebrity Naomi Watanabe dress as a pig for the opening ceremony.

The PR nightmare only served to hurt public sentiment toward the games. A Kyodo poll in May, for example, showed that nearly 60% of Japanese wanted the Olympics to be canceled.

“It’s too late now, but there should have been a unified public relations headquarters handling all Olympics-related inquiries, updates and messaging rather than having a hodge-podge of various parties scrambling to offer explanations every time an issue arose,” says Akio Yamaguchi, a crisis management consultant.

Adding to the confusion was the uncertainty over who had the authority to make the final decision concerning whether and how the games would be held, Yamaguchi says.

“Is it Koike? Suga? The IOC?” he asks. “Murkiness over the decision-making process only fuels speculation and distrust, something a better-organized PR team could have dispelled to a certain extent.”

And while the economic virtues of the Summer Games have been played up, the coronavirus has dampened such a prospect. Takahide Kiuchi, executive economist at the Nomura Research Institute, estimated that canceling the Olympics would cost Japan around ¥1.81 trillion, but warns of an even larger economic fallout if the games became a superspreader event, necessitating a fresh state of emergency.

Kiuchi, a former Bank of Japan board member, says that the first nationwide state of emergency last spring caused an estimated ¥6.4 trillion in losses. The second round incurred damages of ¥6.3 trillion and the third emergency decree has likely brought about a hit of ¥3.2 trillion.

Meanwhile, organizers have decided to limit the number of spectators to 10,000 fans or 50% of a venue’s capacity, whichever is smaller.

Kiuchi says that even if the games are held without any spectators, it will result in an estimated ¥1.66 trillion in economic benefits, around ¥146.8 billion less than if they are held with domestic spectators.

“The economic impact of limiting spectators is negligible,” Kiuchi says.

“There are experts who warn that the games could trigger clusters of infections,” he says. “Our estimates suggest that these decisions should be based on the standpoint of infection risk, not economic loss.”

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

SUBSCRIBE NOW