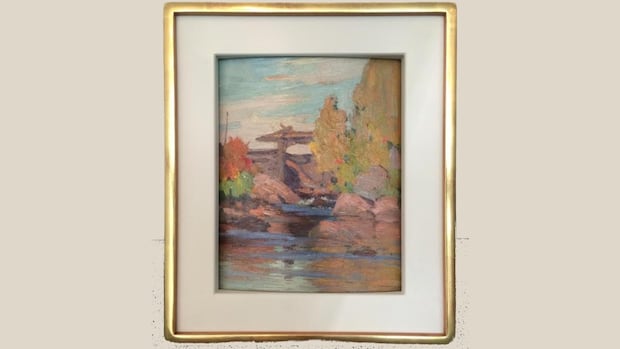

It’s been about a decade since Michael Murray saw the painting of Tea Lake Dam he received from his uncle in 1977 — a piece he says is an original Tom Thomson and whose disappearance sparked an $11-million lawsuit with a Toronto auction house that claims it never accepted the alleged masterwork.

A gift following Murray’s graduation from medical school, the painting hung in his uncle’s Ottawa home, a property he inherited from Flora Scrim, the owner of a local flower shop where he worked. The painting came with the estate and Murray says it’s believed it was a gift to Scrim’s brother from the renowned Canadian painter Tom Thomson.

Michael Murray is suing Toronto’s Waddington’s Auctioneers & Appraisers, alleging conspiracy and neglect in connection with the disappearance of his painting which he claims is an original Tom Thomson.CBC’s Farrah Merali has the story.

But though he can trace how the 8×12-inch painting came into his family’s possession, neither Murrary nor a private investigator can find what happened to it, they say, since it was sent to be sold at Waddington’s Auctioneers & Appraisers.

“I felt stupid — taken advantage of,” the 74-year-old told CBC News in a recent interview.

The suit alleges the painting’s disappearance was caused by “gross negligence” and alleges the auction house and a former employee “conspired one with the other” to withhold the painting from Murray.

None of the claims have been tested in court. In its statement of defence, Waddington’s denies the allegations, saying the painting was never at the auction house. It also questions the authenticity of the painting, which is a small, colourful landscape believed to be depicting Algonquin Park’s Tea Lake Dam in Ontario.

Changing of hands

Murray told CBC News he and his wife decided to sell the unsigned painting more than a decade ago and began the process of having it authenticated. In 2013, Murray — who works as a physician in Hawaii — had the painting sent to the National Gallery in Ottawa to be reviewed by the conservation science division of the Canadian Conservation Institute.

Staff there analyzed the paint and found a pigment called “Freeman’s White” — a pigment that has only been found in paintings by Thomson and the Group of Seven, according to the staff report, which was viewed by CBC News.

“This strongly supports the attribution to Tom Thomson,” the report reads.

According to the statement of claim, in April 2014 the painting was also examined by a University of Toronto art historian who attributed it to Thomson. In summer 2014, according to the claim, the painting was sent for restoration and then delivered to Toronto’s Nicholas Metivier Gallery in July 2014.

Gallery owner Nicholas Metivier, who declined to speak to CBC News for an interview, recommended the services of Waddington’s in Toronto in 2015, Murray told CBC News. Metivier also introduced him to Stephen Ranger, at the time the vice president of business development for the auction house and appraiser, he said.

“It was all credible references, each step of the way,” Murray said.

Murray said he exchanged emails with Ranger, in which Ranger agreed to manage the sale at a fall 2015 auction, but Murray said he didn’t receive any official paperwork from Ranger or from Waddington’s.

The statement of claim says Murray inquired about the progress with Ranger, who “consistently” confirmed the painting was with Waddington’s, but then in 2017 Murray was told the painting would be temporarily placed in storage. Murray told CBC News he didn’t contact Waddington’s for a few years due to health issues in his family.

In 2021, after Murray claims he made “numerous” inquiries to Waddington’s he received an email from a representative of the auction house indicating the painting was not there.

“It took quite a while for it to sink in,” Murray said. “I was thinking, ‘Where’s my painting?'”

Appraised at $1.5 million

In early 2022, Murray contacted Steven Bookman, managing partner of Bookman Law, for help.

“There’s strong evidence in writing through emails and other communications that it was in [Waddington’s] possession,” Bookman said in an interview with CBC News.

“We have very little concern about establishing the validity of this as a real Tom Thomson.”

That same year, Murray hired an appraiser to review available documentation related to the painting and to assess the existing photographs. The appraisal report, viewed by CBC News, estimated the painting’s value at $1.5 million.

“The last value we had was in 2022. These paintings by Tom Thomson are incredibly in demand, so I don’t know if it’s gone up since then.”

Waddington’s response

CBC News reached out to Waddington’s and its president Duncan McLean and received a response from their lawyers stating: “As this matter is currently before the courts, we cannot comment at this time.”

However, in a statement of defence filed in response to Murray’s lawsuit, Waddington’s denies the painting was ever at its auction house, saying that when it takes possession of any artwork it provides a receipt and enters that data into its system.

“No such records exist for the painting,” the statement says. “The painting was never kept on Waddington’s premises to the best of the defendant’s knowledge.”

The statement of defence also denies the painting is by Thomson or “that it has any real monetary value.” It claims Waddington’s and McLean made inquiries about the painting in July 2021 and that they were advised by “external authorities” that it was not authenticated as a work of Thomson.

In the court documents, Waddington’s alleges it learned in 2020 that Ranger was running his own business in competition with Waddington’s and his employment was terminated — claims that have not been verified by CBC News. When reached for comment by email, Ranger told CBC News: “I left Waddington’s five years ago so would have no idea of the whereabouts of this painting.” He didn’t respond to a further request for an interview.

In his statement of defence, however, Ranger said he picked up the painting in his capacity as a vice president at Waddington’s and says he delivered it to Waddington’s. He claims the painting was still in Waddington’s possession in storage at the time of his February 2020 departure. The statement of defence goes on to say: “At no time did [he] remove, sell or dispose of the painting from the premises of Waddington’s.”

‘Opaque’ industry and challenges

In 2021, Murray hired Haywood Hunt & Associates to try and track down his missing painting.

“People who may or may have possessed that painting at any point in time — they weren’t eager to admit that they had the painting,” said Jeff Filliter, senior investigator with the private investigation agency, and the lead on the case.

“Some of them reluctantly said, ‘Yeah, we had it for a while, but it’s gone on.’ So the challenge was to try and nail down precisely when the painting went from point A to B to C.”

Filliter said what struck him was a lack of eagerness by many to share information.

“It got to a point where when we talked about possession of the painting, everybody kind of threw their hands up and said ‘No, it’s not me, it’s not me,’ which I found a bit odd,” said Filliter.

He said he did make inquiries about a possible sale of the painting on the dark web or in the black market, but to no avail.

“Through every passing of time, it becomes that much more difficult to find an object because of the elusive nature of the art market, because of the opaque nature of it,” said Det-Const. Lionel Doe with Toronto Police Services. Doe is not involved with the civil suit, but he completed a postgraduate program in art crime in Italy — the only member of the police service with such training.

“If there’s no paper trail or vague paper trail to follow, adding more time to it makes it that much harder to find.”

But in certain cases, Doe says the passing of time can help in retrieving a stolen painting, though it has not been proven that Murray’s painting has been purposefully taken.

“If it is a high-end painting or a masterwork, it appreciates at a level that will kind of force it to the surface eventually because of the temptation to sell,” Doe said

A trial date has not yet been set for Murray’s lawsuit, which was filed at Ontario’s Superior Court of Justice in March 2022.

While Murrray said he regrets not asking for more paperwork from Waddington’s at the time, he said he felt confident that at every step he was referred from one credible expert to another, saying he’s not sure what he could have done differently.

“I was very trusting that I’m dealing with honest, upfront people,” said Murray. “I feel betrayed.”

If you have tips for CBC Toronto’s investigative team about this story or others, get in touch at torontotips@cbc.ca