This is a sponsored story, created and edited exclusively by Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Tokyo Updates website.

How Japan surprised an American zoologist

In 1877, a visiting American zoologist named Edward S. Morse was surprised to see how kindly people treated animals in Tokyo. “It was unimaginable in the USA that rickshaw drivers would go out of their way to avoid cats and dogs on the street. He was also intrigued by people referring to cats with ‘-san‘ (a Japanese honorific used generally for addressing people),” says Koyama. This kind of relationship with animals is still fairly normal in modern-day Japan.

“A Collection of Happiness, Customs in the East: ‘Lucky Mice'” (1890) by Yoshu Chikanobu, portraying women playing with white mice, which were said to bring good fortune

| Courtesy of Edo-Tokyo Museum

Keeping small animals was one of the pleasures common people in the Edo Period enjoyed, but surprisingly, mice were also cherished as pets. “Back then, people kept mice like we do now with hamsters. They were considered messengers of Daikokuten, the god of good fortune, and were appreciated by people,” Koyama explains.

“The exhibition is entirely from the Edo-Tokyo Museum’s collection,” said Koyama.

| Yoko Akiyoshi

On the other hand, they were also a nuisance: There is a story that mice ate up all the rice in a house, leading to the downfall of that family. “Animals are not just cute. Their relationship with humans is a little more complicated than that. They are cute, but sometimes they also cause trouble. You must accept that in order for things to go smoothly.”

Why did people refer to cats with ‘-san’?

Cats were also popular, but they were “more than just cute creatures,” Koyama says. “There are many legends of bakeneko (monster cats) in Japan. Even long ago, people must have felt that cats are not only cute but mystical, too. They were also somewhat revered, as there is some folklore including cats that could understand human language. I believe they were referred to with ‘-san’ for these reasons.”

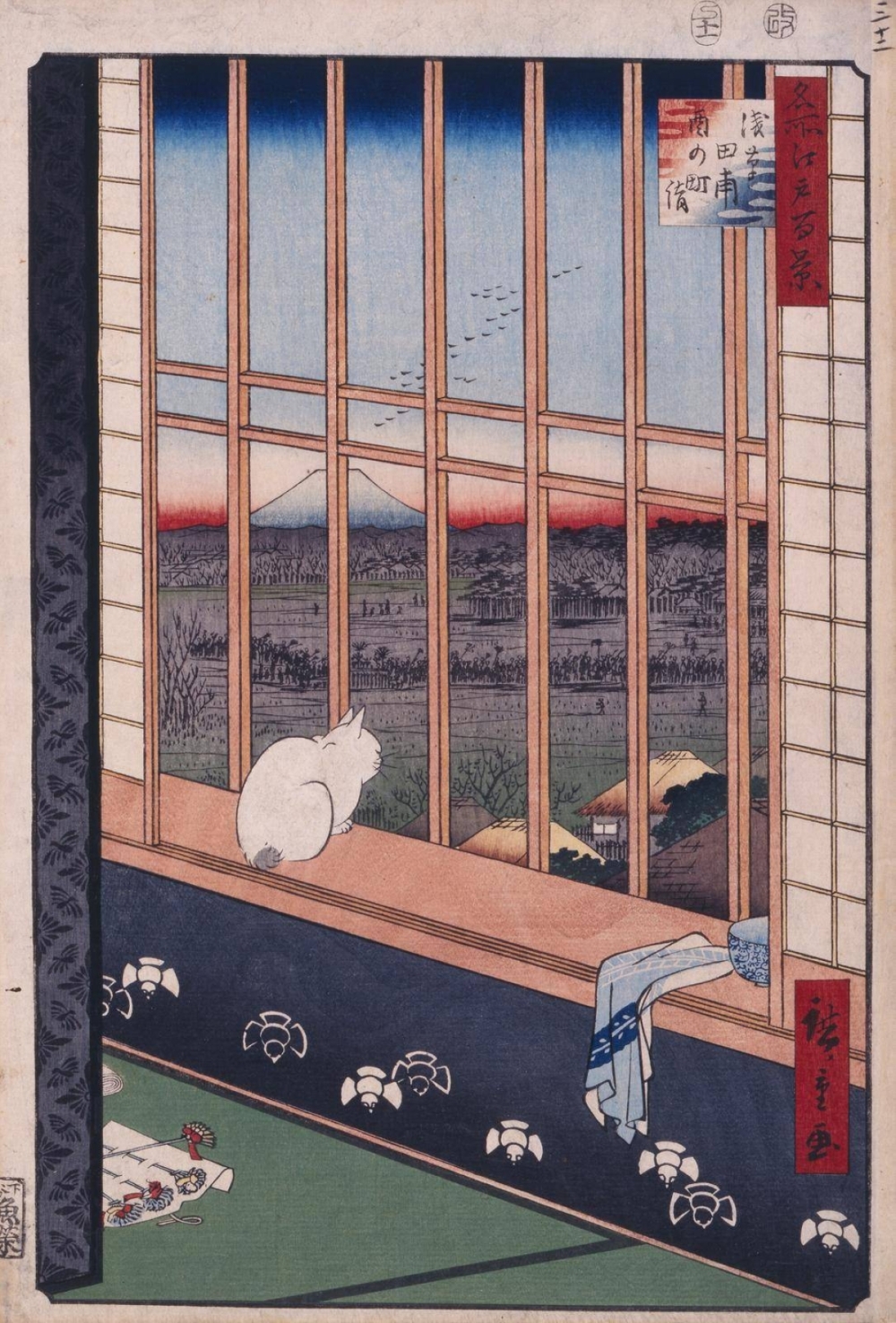

“One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Procession for the Tori-no-ichi Festival, Asakusa-tanbo” (1857) by Utagawa Hiroshige, a popular work at the exhibition portraying a cat looking out through a window.

| Courtesy of Edo-Tokyo Museum

We can also deduce that cats were special from the technique used to depict them. “In ukiyo-e, cats are portrayed with a printing technique that makes them seem three-dimensional. If you look at the prints in person, you can see how fluffy they appear.”

You may wonder, “What about dogs?”

“In Edo (the city, now Tokyo), there were not many people who kept dogs as a personal pet. There were so-called machi-inu (town dogs), that were taken care of by the entire town. They served as guard dogs for the town, played with the children and were fed by the townspeople. Ukiyo-e from the Edo Period often include machi-inu.”

“Funabashiya Confectionery in Sagacho, Fukagawa” (1839-1841) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, portraying dogs that were part of the community

| Courtesy of Edo-Tokyo Museum

Works from the Edo Period also include various wild animals such as deer, cranes, storks, and Japanese river otters. “There is a record that the third shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu, hunted as many as 2,135 deer in a year and a half. Although the Japanese river otter is not in paintings, the 1824 book ‘Buko Sanbutsu Shi’ (List of Animals and Plants Found in and Near Edo) says that the now-extinct animal was living at the Genmori Bridge. This is a bridge known as a photo spot for Tokyo Skytree in Sumida City. Two hundred years ago, Japanese river otters swam under that bridge. Isn’t it interesting?”

French people’s impressions of the exhibition

This exhibition is an expansion of the exhibition held at the Japan Cultural Institute in Paris in 2022, titled “Un bestiaire japonais — Vivre avec les animaux à Edo-Tokyo (XVIIIe-XIXesiècle)” (A Japanese Bestiary — Living with Animals in Edo-Tokyo During the 18th-19th Centuries). What was the response in France?

“One of the things that attracted attention was a notice board related to the Edicts on Compassion for Living Things issued during the reign of the fifth shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi. It states that anyone who abandons a sick horse that is not expected to recover will be punished by death.

“Quail Meeting” (late Edo Period) by an unknown artist, portraying one of the quail singing contests that became popular as the number of fans increased starting in the early Edo Period

| Courtesy of Edo-Tokyo Museum

In Europe, animal welfare has become widely established only in recent years, but they were surprised and said that they had never heard of someone like a shogun giving such an order in that era,” Koyama said. This echoes the experience of Morse, who was surprised by the amicable relationship between Japanese people and animals.

French people also had an interesting take on the status system during the Edo Period. “They were surprised by a piece that portrays a quail singing contest because bird owners were all sitting together regardless of status, with no separation between samurai with katana and merchants. It was interesting for the French to see the equal relationship between people when it came to entertainment.”

Rare animal shows became popular

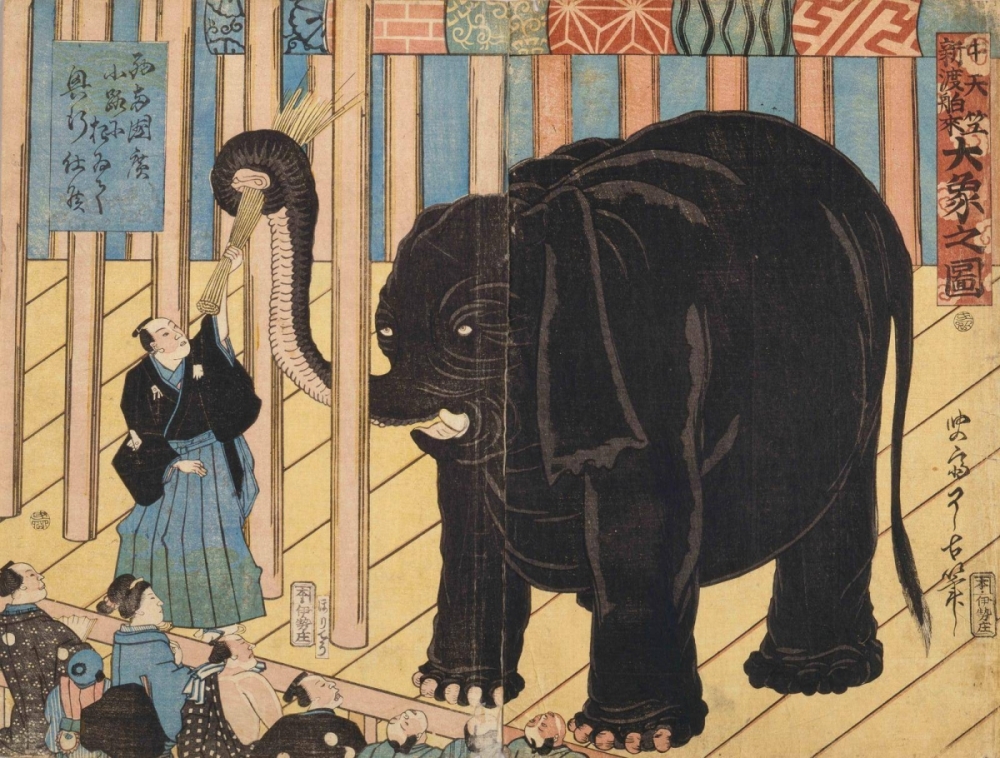

The exhibition includes many paintings that portray shows of rare animals such as elephants, camels, tigers and leopards. “The Edo Period saw a rapid urbanization. By the 18th century, Edo had become a city with a population of over one million, and the field of entertainment was well developed.

Although Japan was isolated at that time, many animals were brought in from overseas and were shown at show huts in the entertainment district near Ryogoku (in eastern Tokyo). You can see how excited people were, with some looking up at the elephant so much that their necks would snap. I hope visitors will glean the excitement of the people from that time from the print.”

“Newly Imported Large Elephant from Central India” (1863) by Ryoko, portraying a female elephant imported through Yokohama

| Courtesy of Edo-Tokyo Museum

Koyama, who has curated many ukiyo-e exhibitions, concluded the interview by describing the appeal of Tokyo: “During the transition from the Edo Period to the Meiji Era, the city was not destroyed, and now traces of the Edo Period remain across Tokyo. These include the names of roads and bridges, as well as parks and schools with echoes of daimyo (feudal lords) residences. I think Tokyo is a very rich city in that it has cutting-edge things, but also allows us to think back to the Edo Period.”

The exhibition “Animals, Animals, Animals! From the Edo-Tokyo Museum Collection” will tour in Aichi and Toyama Prefectures in 2025.

Translation by Toshio Endo