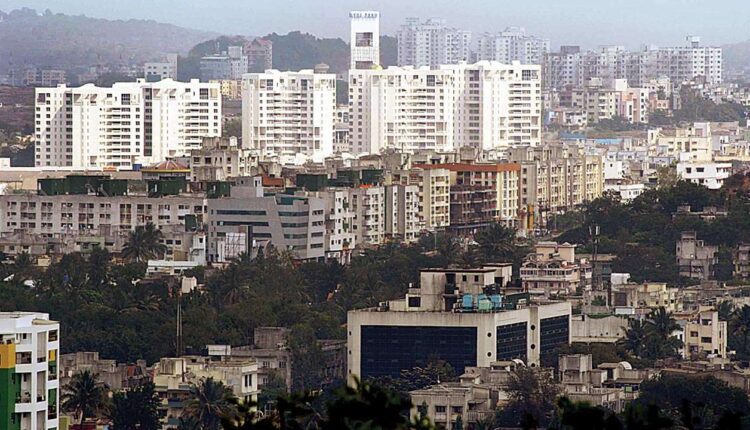

Postcards From The Past: When Shivajinagar was once ‘fields of sugarcane and mud houses as in any village’

Jangli Maharaj Road, a 2.5-km stretch between the Sancheti Hospital crossing and Garware Bridge, is one of the busiest streets in Pune today. But what only an earlier generation and heritage enthusiasts know is that this road was once a case study in civil engineering as well as the result of an audacious move by the municipal corporation.

In 1973, this road was in a state of complete disrepair. It was so dangerous, particularly after rainfall, that the then chairman of the municipal corporation’s standing committee, Shrikant Shirole, asked a civil engineer why Pune’s roads could not withstand a shower like those of Mumbai. The answer, Shirole recalls, was “Hot Mix”, a new technology from Recondo, a company that was run by two Parsi brothers.

Shrikant Shirole still works sitting under an image of Chhatrapati Shivaji in his office. (Express photo by Pavan Khengre)

Shrikant Shirole still works sitting under an image of Chhatrapati Shivaji in his office. (Express photo by Pavan Khengre)

The next time Shirole was in Mumbai, he visited Recondo’s office in Panvel. His next move was bold — the standing committee awarded the project for redoing JM Road directly to Recondo without calling for tenders. The company’s response was equally bold — they gave a written warranty that the road would not develop any problem for 10 years “or they would repair it for free”. Shirole says it’s a mark of the commitment and workmanship of an earlier era that JM Road, which opened on January 1, 1976, did not need repairs until 2013. “I still travel by that road every day. And it is still one the best roads in Pune city,” he says.

In 1968, Shirole recalls, he was one of the youngest members of the Pune Municipal Corporation, at the age of 21. Today, he is an established criminal lawyer and works out of an office in Shivajinagar — built at the spot where his ancestral wada used to stand. “All this used to be farmland. There were fields of sugarcane and mud houses as in any village,” he says.

Shirole was born in 1946 at Phaltan in Satara, in his mother’s maternal house as was the custom for the first pregnancy at the time. His father’s family were landlords of the vast expanse of Bhamburde village, an area now known as Shivajinagar. The family had come to Pune 300-350 years ago. “There is the history I heard from my grandparents about our ancestor, Ratnoji Rao Shirole, who was a part of the army of Shivaji Maharaj. We are from Shirwal tehsil and our original name was Shirwale,” he says.

There is an alternative story as well — that the men in the family formed a part of the Maratha army regiment that was responsible for beheading enemies and the name derives from the local word for head. “We were the ‘sir-kaatney wale’ (the beheaders),” says Shirole, who still works sitting under an image of Chhatrapati Shivaji. Another image of the great Maratha is present on a shelf.

Shirole’s father, Bhausaheb Shirole, was a mayor in 1957-58. As a child, Shirole lived with different generations in the family in a three-storey wada that had been built during the Peshwa era, and had more than 20 rooms and open spaces for the five children. “My grandmother used to take us to the ‘city’ because Shivajinagar used to be considered the outskirts. Whenever we said that ‘we were going to the city’, it meant that we were crossing the bridge to go to Kasba or Laxmi Road,” says Shirole.

But there were also some traumatic moments. Shirole points to the ceiling of his office and says, “That was the level of water when the Panshet dam disaster took place. July 12, 1961 started as a regular morning at Modern High School, except that as soon as prayers were over, the class-teacher told the pupils to go home as there was going to be a flood. They didn’t tell us that the Panshet dam had broken and there was going to be a calamity. It was the rainy season and we thought that there would be a small flood,” he says.

The children ran all the way home, tossed their bags and went to see the water. “We thought, ‘Kitna paani aa sakta hai (How much water can be there)?’ As soon as I went to Congress Bhavan, I saw the water was rushing towards us, driving us back. Till then, nobody had even heard the word Panshet. We knew Khadakwasla. Today, we know that Panshet dam was much larger than Khadakwasla,” he says.

At the time, Shirole’s mother and a pregnant aunt were in their maternal homes. His father was in Bombay on work. By the time the waters engulfed their home, the family had escaped with only their lives. “All houses were of mud at the time and no family could salvage their valuables. Everything was swept away,” he says. Shirole recalls standing on the high platform of a Ganesh mandir and watching his home go down in the water. “Like many people of the time, I can still visualise how houses merged with the water and small pieces of belongings floated out of sight,” he says.

He recalls adults being shocked into silence and rumours circulating that the Khadakwasla dam had also breached. He remembers going back to the site of his home and rummaging in waist-high slush for familiar belongings — and coming back empty handed. Shirole’s parents set off for Pune after hearing that the city had been destroyed. “When my father saw us, he took all of us in his arms and broke down,” says Shirole. Soon, help arrived on trucks laden with food and essentials.

“Even in the city, people helped one another as it was, mostly, the middle-class and lower-middle-class that had been affected,” said Shirole. The Panshet dam disaster would set off a concerted effort in urban planning and led to the development of the city. And, areas such as Shivajinagar and Senapati Bapat Road took on its present shape. A concrete building came up where the Shirole wada once loomed. The event also marked Shirole’s course of life and he became a member of the City Improvement Committee for three consecutive years from 1968.

“In 1968, the price of land in the city was Rs 135 per sq ft and gold was Rs 180 per tola. When I was chairman, the total PMC budget was Rs 11 crore only (in 2022-23, the budget was Rs 8,592 crore). We used to get Rs 150 per month as honorarium and Rs 10 per meeting for five meetings only,” he says.

Shirole, like everybody else, cycled to work in the Cantonment area. “Then, Bajaj came in with scooters and, suddenly, there were only scooters on the road,” he says. Later, he started a petrol pump at Shivajinagar — which no longer exists — and found that there were too few cars. “If a car came in, the worker at the pump would go and clean the glass and ask how much fuel was needed. People bought fuel by the litre at the time. It was 45 paise per litre for diesel and 79 paise per litre for petrol. We used to give a 5-paise discount in 1963. If we forgot, people would ask us,” he says.

Today, the city reflects the different phases of change, from roads flaunting different models of cars to a thriving IT industry. Shirole, too, has transformed — he used to once wear only khadi kurta-pyjama or shirts and trousers and has now graduated to suits of colour. But, every morning, he is still at work under the eyes of Shivaji Maharaj. And, traffic continues to buzz through the day and night on JM Road.