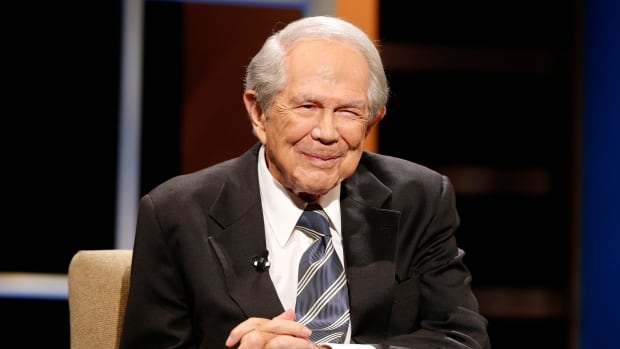

Pat Robertson, who after claiming to be visited by the Holy Spirit in Ontario cottage country developed and hosted 700 Club for nearly six decades, binding the ascendant evangelical movement to Republican Party politics, has died. He was 93.

The death of Robertson, who ran for U.S. president in 1988, was announced Thursday by his Christian Broadcasting Network. No cause was given.

Described as “the most curious and contradictory of all the Christian right leaders” by Frances Fitzgerald in The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, Robertson’s broadcasts didn’t see him thundering from behind a pulpit to an in-person megachurch congregation.

Instead, he harnessed the power of television by communicating in a genial manner to believers from a studio, often directly through call-in segments.

Still, his charismatic brand of Protestantism was far from the mainstream version. Robertson believed God spoke directly to him through the power of prayer and admitted to speaking in tongues on occasion.

He prophesied that the Bible foretold the looming destruction of Israel, which would eventually lead to, as stated in his Christian Broadcasting Network’s promotional material, the “coming of Jesus Christ and the establishment of the Kingdom of God on Earth.”

Homophobic, extremist comments

Robertson convinced callers and studio guests that God was working through him to cure their afflictions, ranging from scoliosis to hemorrhoids, and he once boasted that his prayers had diverted a hurricane’s path.

The CBN’s messages — broadcast internationally, including in Canada — were of personal salvation, biblical inerrancy and a large dose of criticism of secularist trends in society.

Those messages resonated with an overwhelmingly white audience that grew in political activism during the 1970s after being disappointed by the landmark Supreme Court decision on abortion as well as the country’s liberal turn under a Southern Baptist president.

‘I’ll tell you, in those days, under Jimmy Carter, I honest to goodness thought the end was near,” Robertson said years later.

In recent years, Robertson was criticized for a rash of convoluted comments, perhaps most notoriously ones where he tried to connect a Louisiana hurricane and a Haiti earthquake with moral decay, abortion and homosexuality.

In 2006, Israel’s tourism ministry pulled out of a multimillion-dollar deal with Robertson’s organization to build a Christian centre after he described then-prime minister Ariel Sharon’s stroke as “divine retribution” for his withdrawal of troops from Gaza. Robertson in a letter of apology said his “love of Israel” and concern for the country’s future explained his comments.

Presidential bid

Robertson joined other Christian broadcasters led by Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority to give full-throated support to 1980 presidential candidate Ronald Reagan, and then he decided to run to succeed Reagan eight years later.

“I’d be very concerned about a man sitting next to a [nuclear] button who believes Jesus is telling him to press that button,” Gerald Thomas Straub, a former 700 Club producer, wrote in a 1987 book critical of Robertson.

Robertson’s candidacy came three years after he opined that only Christians and Jews should serve in U.S. government positions. He finished ahead of George H.W. Bush in the Iowa primary but claims that he embellished his Korean War service while in the Marines helped doom his campaign.

In the early 1990s, Robertson’s Christian Coalition would become heavily involved in political campaigning against Bill Clinton’s administration, advising Christians on Republican candidates that espoused friendly policies as the party romped to big gains in the 1994 midterms.

As the internet spread news faster beginning in the 1990s, his frequent extremist comments began to draw more rigorous scrutiny.

While Robertson’s organization would dole out significant humanitarian aid around the world through its Operation Blessing initiative, 700 Club segments would often feature his unpredictable opinions on subjects ranging from Islam (“The goal of Islam, ladies and gentlemen, whether you like it or not, is world domination”) to Halloween (“The day when millions of children and adults will be dressing up as devils, witches and goblins … to celebrate Satan”).

His 1991 book The New World Order was put under the microscope in articles for its frequent use of antisemitic tropes, as it described conspiracies of shadowy Illuminati figures and globalists to explain much of human history.

Robertson, whose organization had once helped fund Nicaragua’s right-wing Contras, also called for the assassinations of Libya’s Moammar Gadhafi and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez.

‘In the wilds of Canada’

Robertson was born on March 22, 1930, in Lexington, Va., and gave no indication of his future path while attending a military academy and a liberal arts university.

“He drank as much as most college kids,” a former classmate told a reporter during the 1988 campaign.

His religious awakening occurred well into his 20s. A young man of means — his father served for over three decades in the U.S. Congress — he was influenced by a fundamentalist bible teacher, Cornelius Vanderbreggen.

In the late 1950s he took a monthlong religious retreat at the Camp of the Woods in Lake of Bays, Ont., and described what transpired next in the 2020 book, I Have Walked With the Living God.

“It was in the wilds of Canada that I began to feel the presence of the third person of the Trinity, the Holy Spirit,” he wrote. “It’s hard to define the feeling, but it was clear to me that He was introducing Himself to me.”

Robertson returned home, and after a brief time as a youth minister, bought a Virginia television station for $37,000 US in 1961 to broadcast religious programming.

The station was not an immediate success, but the 1963 hiring of popular hosts Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker sparked ratings. The Bakkers would leave in the 1970s for their own ventures, but by then the 700 Club was a television institution and Robertson had snapped up other independent stations.

Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network would fill time slots around its religious programming with wholesome syndicated fare like Leave It To Beaver and old westerns.

What became known as The Family Channel (not to be confused with the Canadian network of the same name) had to be spun off into a separate company so as to not jeopardize the organization’s non-profit status. The channel was sold to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation in 1997 for $1.9 billion US.

Trump defender, then critic

After Democrat Barack Obama succeeded born-again Christian George W. Bush as president, a backlash emerged that pushed Republican politics rightward.

Donald Trump won the 2016 election with support among evangelical voters estimated at 81 per cent, as many believers overlooked Trump’s extramarital affairs and frequent examples of un-Christian behaviour.

Robertson and Trump had commonalities despite their difference in piety — both were ambivalent at best about the role of the United Nations, and each campaigned on upping military spending and eliminating trade deficits. Above all, both focused on standing up for Israel, promoting pro-life views and appointing conservative judges.

Robertson downplayed the Access Hollywood recording in which Trump boasted of committing sexual assault, saying he was just “trying to look like he’s macho.”

Robertson was occasionally critical of Trump, as when the president decided to send troops into states to deal with protesters in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

“You just don’t do that, Mr. President. It isn’t cool,” said Robertson. “We are all one race and we need to love each other.”

As Trump perpetuated the lie that he won the Nov. 3, 2020, election, Robertson had seen enough, describing Trump as living in “an alternate reality.” Former South Carolina governor Nikki Haley would be a better 2024 candidate, he said.

Robertson was predeceased by wife, Dede, who died in April 2022 at age 94.