The people of Fort McMurray in northeastern Alberta have seen their share of tough times over the last decade — a fire, a flood, COVID-19 and an oil crash. One restaurateur joked last year he hoped locusts weren’t next.

But more than one year later, the oil and gas industry’s fortunes have changed significantly, lifted by record profits. The situation has also buoyed the expectations of some of those who live in the community.

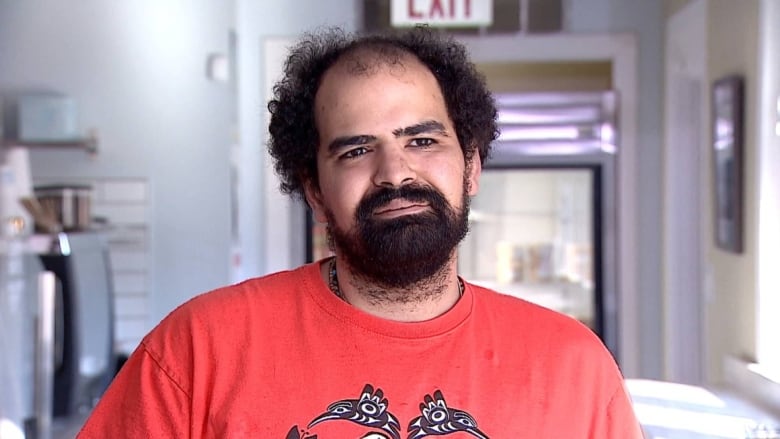

Owen Erskine, owner of Mitchell’s Cafe in downtown Fort McMurray, said the community seems to be the first to experience the highs and lows of Alberta’s boom-and-bust oil industry.

Today, he’s seeing some encouraging signs — like Syncrude moving more employees downtown, and more municipal and provincial government employees present in the community.

“I think we’re seeing a lot of optimism, of course, with oil and gas being our main sector up here,” Erskine said.

Optimism is a welcome relief to residents of a community that has gone through many challenges, but what seems clear is that the oilpatch is not splashing around investment like it did amid previous oil booms.

Though companies have been reporting record profits this year, the proportion of oil and gas reinvestments back into the Alberta economy are a fraction of what they were at the time of the last boom.

The ARC Energy Research Institute, which models the entire western Canadian sedimentary basin, projects the industry will produce $250 billion of revenue this year, almost two times the typical level seen over the past decade on average.

Almost all cash flow used to go back into capital spending, said Jackie Forrest, executive director of ARC. Today, only one third is going back.

“So [capital expenditures] is a fairly small number here. We’re expecting about $42 billion of capital spending this year, which is really down relative to the average over the last 10 years,” she said, adding that over the past decade a typical level might have been $60 or $70 billion.

Even in communities where oil and gas activity is picking up, trepidation about the future remains. Jason Schneider, the reeve of Vulcan County, located southeast of Calgary, said the area sits on some established oil and gas fields, and people are busy again there.

“Definitely everybody’s being a little hesitant and pretty cautious this time around, because I think they’re just kind of trying to use what they currently have,” he said.

“But as far as new investment, we’re not really seeing much in this part of the province.”

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) said industry had generated an estimated $35 billion to $40 billion in domestic capital investment this year.

So what’s changed?

Charles St-Arnaud, chief economist at Alberta Central, the central banking facility for the province’s credit unions, said oil producers are using their revenues in very different ways compared to 2014, part of which has to due with the fact that current revenues have been redirected to pay debt accumulated during the pandemic and the oil price collapse.

“In 2014, about four per cent of revenues were being returned to shareholders,” St-Arnaud said. “Now, that proportion is closer to 10 per cent.”

The big difference is that about 75 per cent of those shareholders are not Canadian, meaning the money is flowing almost completely out of the province and Canada, according to St-Arnaud. Though there’s about 25 per cent left over, those shareholders are spread across all of Canada, not just Alberta.

In St-Arnaud’s view, that trend is linked to forecasts for global oil demand, which is projected to peak in the early 2030s and then start to gradually decline.

Oil producers, therefore, are no longer in a position where they may be inclined to dramatically increase production each time revenues and profitability increases.

In a statement, CAPP pointed to a recent analysis by investment firm Peters & Co. predicting that the oil and gas sector will return approximately $50 billion in the form of royalties and taxes to Canadian governments in 2022.

“These contributions to the Canadian economy support hundreds of thousands of jobs and help fund infrastructure, health care, schools, roads and critical social programs across the country,” said Lisa Baiton, president and CEO of CAPP, adding that the estimated completion of the TMX pipeline in 2023 will offer an additional transportation capacity of 590,000 barrels per day.

“Canada’s oil and natural gas industry is proud to be a foundational pillar of the country’s economy and a source of opportunity and prosperity for all Canadians.”

What does it mean for Alberta?

What it all has resulted in is a lower level of oilfield activity, construction and jobs that have been seen in past periods of higher oil prices.

“It means we aren’t going to be growing production, because ultimately, if you don’t put the money into the capital programs, you’re probably not going to grow,” Forrest said.

Forrest said companies are also not growing because of limited takeaway capacity, as the province currently does not have access to pipelines to take more supply away from Western Canada.

Although oil prices look good right now, Forrest said investors are more concerned about the long term. In addition, even though less money is being spent, there hasn’t been a lot of new investment in equipment — which can provide some constraints.

“We just don’t have the ability to grow like we might have 10 years ago, because we don’t have those people, those engineering companies, that equipment necessary to do it at the pace that we did before,” she said. “And so it is just kind of interesting at these lower spending levels that we’re seeing some of these constraints.”

St-Arnaud agreed that the nature of the oil industry has changed, in his view, likely forever.

“If we don’t have a boom, that means that probably the bust will be smaller,” he said. “The oil industry will still be there in 2030. But it will take a smaller share of our economy.”