Tampa, Florida – Mieko Kawakami is the reigning queen of contemporary Japanese literature for good reason.

Her fiction grapples with essential questions of humanity, while grounding her characters in a muddy reality populated by broken families, absent fathers and children struggling to find meaning in a hostile world. In “Heaven,” newly translated into English by Sam Bett and David Boyd, the writer melds philosophy and truth into a lacerating examination of power, ultimately asking: Who wields it, and why?

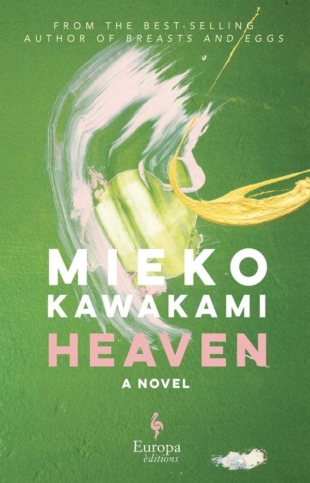

Heaven, by Mieko Kawakami

Translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd

192 pages

EUROPA EDITIONS

On the surface, the plot of “Heaven” is familiar. Two 14-year-old victims of bullying at their local middle school form a tenuous, secret friendship. Under Kawakami’s probing investigation, however, the familiar soon upends into layered explorations of faith, ethics and love.

In an interview with The Japan Times, Kawakami says she intended the novel to be read on multiple levels, inspired by the writings of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche.

“I wanted to create a story that examines how religion, ethics and friendship influence human relationships,” she says. “Do we live our lives under the guidance of something bigger, like spiritual or ethical beliefs, or do we live as individuals?”

The novel’s philosophical bent is not surprising, as her fiction — including “Breasts and Eggs,” Kawakami’s acclaimed full-length English-language debut released last year — shares characteristics of writings by Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse, with frequent conversations or inner musings that scrutinize assumptions and accepted beliefs. In typical Kawakami fashion, there are no pat answers in “Heaven,” only various perspectives, questions — and hope.

The novel’s narrator, known only as “Boku” (me) or “Eyes,” the nickname his tormentors give him due to his lazy eye, dispassionately guides readers through his daily minefields; back slaps and shoves, taunts and casual cruelty that escalate to forced-feedings of chalk, prolonged confinements in a closet and harrowing “games.”

The narrator’s acceptance of recurring violence is bleak, but his helplessness is challenged by Kojima, a fellow victim bullied for her lack of hygiene and dubbed “Hazmat” by the girls in her class. In the opening pages of the novel, Kojima reaches out to the narrator, offering friendship through a letter. Their correspondence provides comfort to the damaged youths — and to readers eavesdropping on their tender missives. As the novel progresses, however, what Kojima really extends is a fierce counter-perspective to the narrator’s passive resignation.

Kojima is the novel’s most compelling character, and her borderline-fanatic idealism, as she struggles with her shame and love for her estranged father, is both appealing and repelling. The depths of her strength, her unwavering beliefs and her ultimate weapon, joy, is reason enough to read this novel.

Kawakami agrees. “Kojima is a great character,” she says. “Other people write about girls who are martyrs, but they’re always portrayed as outwardly beautiful with some fragile weakness. I didn’t portray Kojima this way. She’s not exceptional by typical standards, even to Boku, but she is a girl with great potential and is one of my favorite characters. She embodies friendship and faith.”

If Kojima provides a zealous critique of violence and the ugly absolutism of Nietzsche’s philosophical concept of the “will to power,” Momose, a member of the main bully’s gang, offers a coldly ethical argument for power’s insidious allure. A quintessential bystander who observes violence but does not intervene, Momose is a character readers may love to hate, but he is also the most familiar. How many of the cruelties of power in daily life are justified as inevitable? But as “Heaven” forcefully asserts, readers must find another way.

“The highest number of suicides among young people in Japan is around the last day of summer vacation,” Kawakami explains, adding that the nature of bullying has changed over time, with much of it now taking place online rather than in person. “In the old days, there were just two places for relationships — home or school — but now with social media there is nowhere to hide and the pressure is constant. Victims of bullying think the whole world knows they’re being bullied. It’s even crueler today with the way it can be spread.”

Toward the end of the novel, Kojima and Momose’s beliefs blur, while the narrator is left with the simple power of his individual choice. If Kawakami holds any clear conviction, it may be the power of compassion. Throughout the novel, the narrator quietly chooses to parcel out genuine kindness. And with Kawakami’s empathetic characterization, even the indefatigably cruel bully, Ninomiya, finally reveals his own youthful insecurity.

Kawakami leaves readers then with a final lingering question: Are bullies the result of a society that hands over power so completely to the beautiful, the wealthy and the talented, like Ninomiya? Ultimately, the narrator chooses to see clearly, and the allegorical instruction to readers is equally clear: We cannot turn away from our own dark cruelties.

The novel’s depiction of bullying makes for a disturbing read, and its unsparing authenticity has resonated with readers and critics alike. In Japan, “Heaven” won both popular acclaim and the 2010 Murasaki Shikibu Literary Prize; an early reaction from Kirkus Reviews calls it “an unexpected classic.”

“Heaven” deserves such elevated praise. It defies easy classification and forces the reader to recognize the sinister aspects of human behavior. Kawakami feels it is “her obligation” to reveal this darkness.

“Bullying is a worldwide problem and something that most people have experienced as children. When people grow up, however, the specifics fade and they can’t remember how it could have been handled differently,” she says. “The world of adults and the world of children thus becomes completely disordered and detached. It’s a huge problem and why I feel that it’s my job to write about this difficult age, the teenage years.”

Although Kawakami’s childhood was marked by ostracism and isolation, she says she draws more from her observations as an adult and mother peering into the internal reality of a child.

“I realized how completely different our perspectives are and how we can’t enter each other’s worlds, and it makes me feel extremely helpless,” she says. “I don’t feel that I’ll save any of these children just by writing a novel about them, but it may help awaken readers to the actual situation.”

As Kawakami concludes, “Fiction has the power to reveal options and possibilities, to open up a child’s mind to their choices. I want young people to survive harsh times, not only victims of bullying but also children who are abused by their parents or sexually abused. Children are powerless. … I want them to survive. It’s why I wrote ‘Heaven.’”

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

SUBSCRIBE NOW

KEYWORDS

heaven, Mieko Kawakami