Kyiv and Seoul look to 2 captured North Korean soldiers as potential source for valuable intelligence

Two North Korean soldiers are in custody in Kyiv, bandaged up and under interrogation, after being wounded on the battlefield in Kursk, Russia, over the weekend.

For the Ukrainian military, their capture represents an opportunity to gain insight into the thousands of North Korean soldiers sent by Pyongyang to bolster Russian forces in their fight against Ukraine.

Meanwhile, for South Korea, the first prisoners of war could represent an intelligence coup, in a time when fewer people are defecting from the north to the south.

“I can imagine all the people in the South Korean embassy in Kyiv are celebrating,” said Fyodor Tertitskiy, a lecturer at Korea University in Seoul and an author of a book on North Korea’s military structure.

“These people are from the army and likely engaged in very shadowy … special projects.”

Before this capture, Ukraine’s military had been releasing field notes and passports that it said belonged to North Korean troops and gave a glimpse of how soldiers from an isolated and secretive society operate.

Now, the two soldiers could provide Ukraine and South Korea with much more information.

Part of more than 10,000 troops

The two soldiers were found on Saturday. In a short video released by Ukraine’s Presidential Press Service, one soldier, questioned through an interpreter, said he was told he was going to take part in an exercise, which included training “as if it was real combat.”

“I came out on Jan. 3, saw my comrades die beside me, hid in a bunker, and then got injured on Jan. 5,” he said in Korean, as he laid in a bed with a bandaged hand.

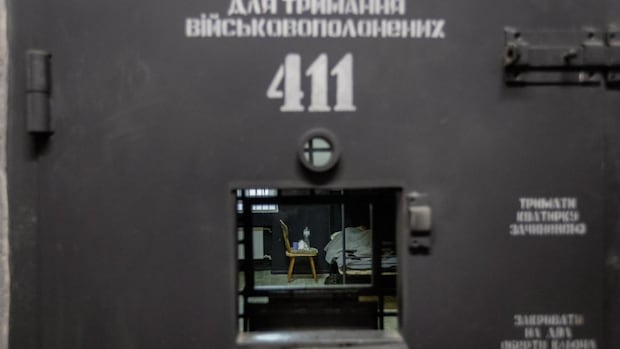

CBC News is choosing to publish a version of the video posted by Reuters, which has blurred the men’s faces to protect their identities, given they are prisoners of war. The content of the video has not been independently verified. The location of where they are being held has not been disclosed.

Ukraine has released a short video that it says are of two North Korean soldiers being questioned in Kyiv after being taken as prisoners of war in Kursk, Russia.

The man with the bandaged hand said he wanted to stay in Ukraine, and asked the person questioning him if he was going to send him home. He said he would go if he were told to.

The other soldier, who had a bandaged jaw, said he wanted to return to North Korea.

According to U.S. and Ukrainian officials, more than 10,000 North Korean troops were deployed to Russia in the fall. Neither Moscow nor Pyongyang has given public confirmation of this, and Ukraine has accused Russia of trying to hide their presence in Kursk by issuing them fake documents identifying them as being from eastern Russia.

The troops, which reportedly include elite and special forces soldiers, were sent into combat late last year. Since then, South Korean intelligence officials say about 300 have been killed and 2,700 have been injured.

The effort is part of what Ukrainian and Western officials see as North Korea’s deepening military relationship with Russia, which also involves the exchange of weapons and ammunition, like short-range missiles.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy says he is ready to exchange the two soldiers to North Korean Leader Kim Jong-un in exchange for Ukrainian soldiers imprisoned in Russia.

Zelenskyy said Ukraine will undoubtedly detain more North Koreans and that there may be an option available for those who don’t want to return home if they “express a desire to bring peace closer by spreading the truth about this war in the Korean [language].”

Tertitskiy says these men are likely better trained than the average North Korean soldier, given that Pyongyang sent some of its elite units.

“It’s not like the [crème de la crème], because these people usually serve as [Kim’s] personal guards. But these are people who supposedly can fight,” he said.

“They are usually well fed and reasonably well trained.”

But he adds that they are extremely isolated, even by North Korean standards, given that as conscripts, they are often prevented from visiting their families for several years.

A potential lack of understanding of modern warfare

A Ukrainian soldier told CBC News that in the beginning of the North Korean soldiers’ deployment, they fought “very badly, like a herd and walked around in large groups in open areas.”

But now, he said, they now appear better trained after working more with the Russians. It’s thought that when the North Koreans were first deployed, they received training and worked digging trenches and in the rear, before being sent into combat in Ukraine.

The soldier, who asked only to be identified by the call sign “Historian,” in keeping with military rules around identification, spoke to CBC over WhatsApp on Monday. He has been fighting in Russia’s Kursk, where Ukraine has recently launched a new offensive in an attempt to regain territory that Russia had recently recaptured.

Issues in the beginning may have been because North Korea’s military structure typically involves the presence of a political officer who signs off on orders given by a field commander before they can be carried out, Tertiskiy said.

North Korea does this to prevent any rogue military action, he said, but on the battlefield in Russia, troops waiting around for orders to be confirmed would have been left at even greater risk.

South Korea’s intelligence agency said that there has been a relatively high number of North Korean casualties given their lack of understanding about modern warfare, and the way Russia has used the soldiers.

Being captured seen as close to treason

Before the two soldiers’ capture, Ukraine had been using other methods to try and show how North Korean forces are operating.

Since late December, the Special Operations Forces of Ukraine has been posting images of handwritten field notes. Ukraine claims they were taken from a North Korean special operations soldier, Jong Kyong Hong, who it says was killed in Kursk on Dec. 21.

While CBC is unable to independently verify the notes, published on Telegram, Tertitskiy has read them and believes they are genuine.

In one note, the soldier wrote that he “will unconditionally carry out the orders of the Supreme Commander Kim Jong-un, even if it costs me my life.”

A different piece of paper shows a simple drawing of three stick figures positioned in a triangle, with apparent instructions on how to shoot down a drone. Another note describes how to avoid being hit by artillery.

For the two detained soldiers, Tertitskiy says if they were returned to North Korea, they would at best face state ridicule for being captured, and at worst, would be quickly executed.

Hyunseung Lee, who used to train North Korean special forces before defecting in 2014, told CBC News he finds it regrettable that Ukraine identified the soldiers by releasing their images.

He says being taken as a prisoner of war is considered a disgrace in the country, almost equivalent to treason.

“Soldiers are taught to choose suicide over capture as an act of loyalty to their leader.”

Ukraine has said it’s seen several cases of this.

Lee, who now works for the Washington-based Global Peace Foundation, said if their identities hadn’t been disclosed, North Korea might have classified them as fallen soldiers, “sparing their families potential harm.”

“Now that their identities have been revealed in the media, if they choose not to return, their families back in North Korea will likely face social repercussions.”