This story is part of CBC Health’s Second Opinion, a weekly analysis of health and medical science news emailed to subscribers on Saturday mornings. If you haven’t subscribed yet, you can do that by clicking here.

Canadian cancer researchers are part of global efforts to test targeted alpha therapy, a new form of treatment that some oncologists believe will become the next frontier in attacking cancer at the cellular level.

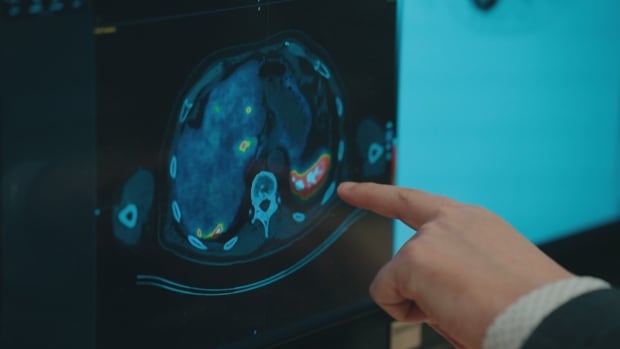

Targeted alpha therapy shreds the DNA of cancer cells by using radioactive alpha particles, which researchers say are more powerful at killing cancerous tumours than comparable existing treatments and less damaging to healthy tissue.

While no targeted alpha therapy has been approved for use outside a clinical trial, several are in the final stages of testing and could be ready for consideration by Health Canada and international regulators within the next few years.

Researchers see its potential in treating pancreatic, prostate and breast cancer, as well as the rarer neuroendocrine cancer, which affects the cells that regulate hormone production throughout the body.

Targeted alpha therapy “is another line of treatment that adds more hope for cancer patients,” said Dr. François Bénard, a professor in the department of radiology at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and a distinguished scientist at the B.C. Cancer Research Institute.

“It can prolong life, reduce symptoms, improve the well-being of people who are affected by cancers,” said Bénard in an interview.

Researchers hope targeted alpha therapy — now undergoing clinical trials in Canada — will become the future of cancer treatment. This therapy seeks out and kills cancer cells without damaging healthy cells.

Targeted alpha therapy falls within the same general category of the cutting-edge cancer treatment known as radioligand therapy, in which specially designed molecules that bond only to cancer cells are injected into the body and release radioactive particles that kill the tumours.

The approved treatments in this category use isotopes that emit beta particles. What makes targeted alpha therapy a potential advance is that alpha particles emit more powerful radiation over a shorter range.

‘Like throwing a bowling ball’

Bénard likens the existing radiopharmaceutical treatments that emit beta particles to throwing golf balls inside a glass house: they can travel quite a distance and cause various bits of damage along the way.

In contrast, says Bénard, targeted alpha therapy “is like throwing a bowling ball. So it will cause a lot more damage, but in a much more limited area.”

Dr. Gerald Batist, director of the Segal Cancer Centre at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, is participating in several clinical trials on treating various cancers with targeted alpha therapy.

“The dimensions of their potential impact are just now being explored,” said Batist in an interview.

One of Batist’s clinical trials is testing a method of treating prostate cancer by embedding beads laden with alpha particles at the site of pancreatic cancer.

Although alpha particles carry powerful radiation, they cannot penetrate the skin, and can even be blocked by something as thin as paper.

As a result, targeted alpha therapy does not have to happen inside the type of protective bunker where traditional radiation therapy takes place.

“I’m very excited about it,” said Batist. “If we can treat people without having to bring them to the hospital, or use these deep bunkers for every single kind of tumour, this represents a very big change for our health-care system.”

3 Canadian sites in alpha therapy trial

Batist is also working on a targeted alpha therapy clinical trial that is taking place in nearly 50 locations around the world, including Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto and London Health Sciences Centre in London, Ont. It’s exploring the use of the alpha-emitting radioactive isotope actinium-225 on neuroendocrine cancer.

In London, the research team led by nuclear oncologist Dr. David Laidley has enrolled five patients in the trial, one of whom became the first person in Canada to be treated with actinium-225.

“Because these actinium particles are extremely powerful and emit a lot of radiation in a very short distance, we’re really able to cause a significant amount of damage to those tumours,” said Laidley in an interview.

“We have a high expectation that the trial will be successful,” he said. “Once it’s been completed, we’ll obviously have to see it go to Health Canada to get approved.”

Multiple companies in late-stage clinical trials

Bénard, who is not personally involved in any clinical trials of targeted alpha therapy, describes it as an evolution in cancer treatment rather than a revolution, because it builds on recent technological advances in creating the molecules that can carry radioactive isotopes to cancer cells.

“What we’re seeing for the first time is multiple companies advancing those compounds through later-stage clinical trials to get approval,” Bénard said. “It’s very exciting because it’s getting much closer to the finish line.”

If and when any treatments are approved, challenges remain in making targeted alpha therapy widely available.

Only a handful of locations worldwide are capable of producing the rare radioactive isotopes that emit alpha particles and can be used in cancer treatment. One of those is TRIUMF, the particle accelerator in Vancouver that’s owned and operated by a consortium of Canadian universities.

Then there’s the cost, expected to run into the tens of thousands of dollars per dose, putting provinces in the position of deciding whether to cover the treatment.

Consider the price of approved radiopharmaceutical treatments targeting neuroendocrine cancer (Lutathera) and prostate cancer (Pluvicto). Both kill cancer cells with the radioactive isotope lutetium-177, which emits beta particles.

Lutathera costs $35,000 per dose, Pluvicto costs $27,000 per dose, with a typical course of treatment for each ranging from four to five doses.

Although Canada’s Drug Agency has recommended that provinces cover both Lutathera and Pluvicto, not all provinces do, and this week, negotiations between the drugmaker and the provinces’ pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance over Pluvicto collapsed without an agreement.

Pharma giants spending billions

One sign of how strongly the pharmaceutical industry believes in the future potential for targeted alpha therapy is the amount of money spent of late in the sector.

“Drugmakers are betting that delivering radiation directly to tumours will become the next big cancer breakthrough,” CNBC reported in September, pointing to some $10 billion US in recent deals by such major players as Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb to buy or partner with companies developing radiopharmaceuticals.

Swiss drugmaker Novartis spent roughly $6 billion US buying the two radiopharmaceutical startups that developed Lutathera and Pluvicto.