The themes that keep drawing Jitish Kallat have, in his words, “persisted or continued to grow in different ways.” These include, “themes of birth, death, time, evolution and decay.”

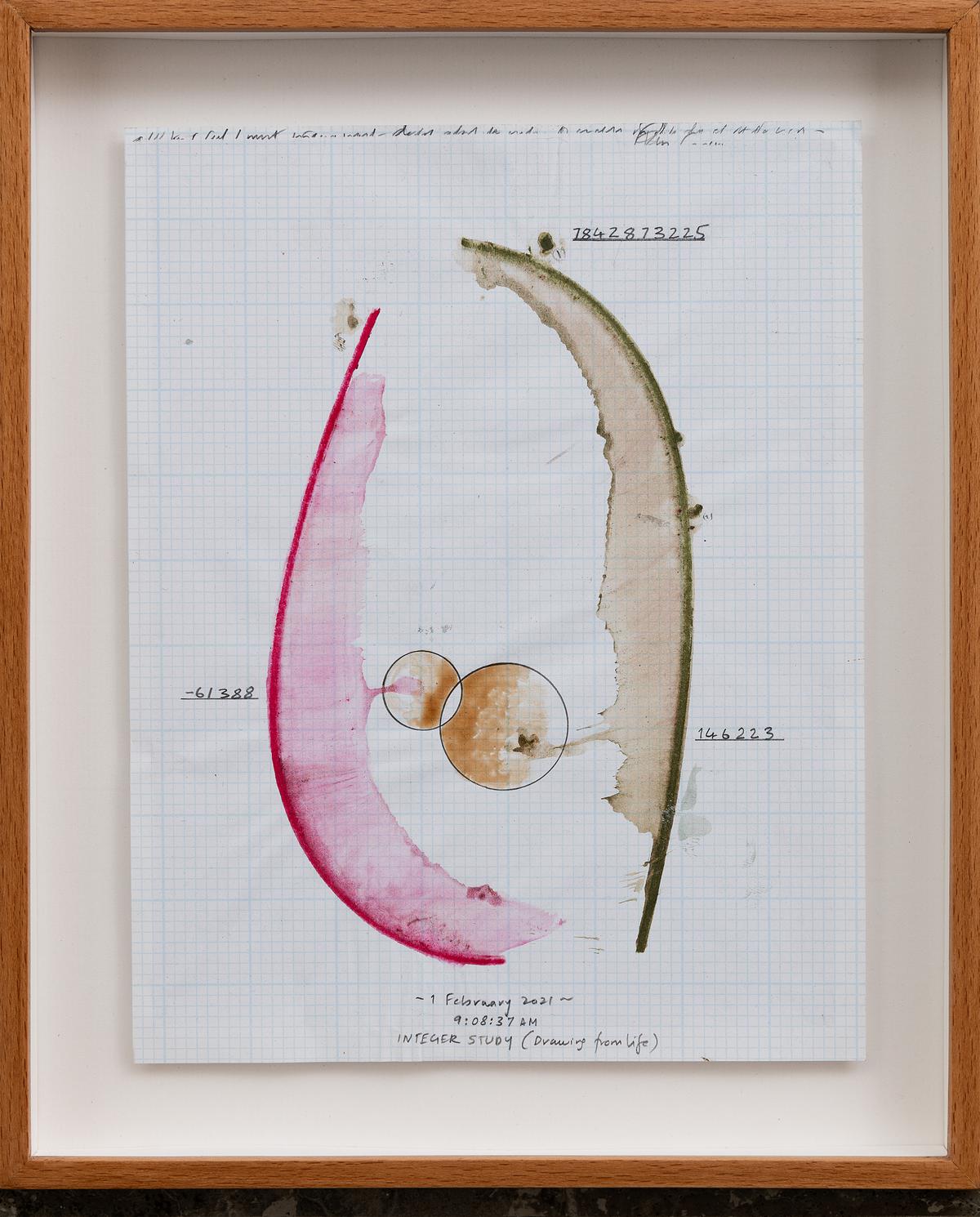

In the 25 years since, Jitish has shown across the world, art that interrogates the fundamentals of life and how humans try and make sense those themes. In ‘Otherwhile,’ his ongoing show at Chemould Prescott Road, the largest work, Integer Study (drawing from life), is emblematic of his inquiry, and the open-ended concepts that let him explore concentric themes. In this case, he explains, he is “counting up our species, moment to moment.” Each study logs the population of the world that day, along with the number of births that day and corresponding number of deaths. The works were made daily throughout 2021, on Bienfang gridded paper.

From ‘Epicycles’ on display at the Chemould Prescott Road

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

This sustained, daily engagement with the three numbers almost anchors every drawing. It also produced a set of intuitions every time he drew, says Kallat. The numbers though, become abstractions, divested of context.

Yet for Kallat, the daily tradition led to questions like, “Where did these ever-growing numbers come from? Every four days there is a million more in that number. Every drawing as a negative integer — where did these numbers go?” Later in the interview, Kallat seems to answer his own question when he says, “Drawing and painting are hardly the tools with which those fundamental answers can be entirely grasped, except by producing certain conditions within imagery that might point to those questions.”

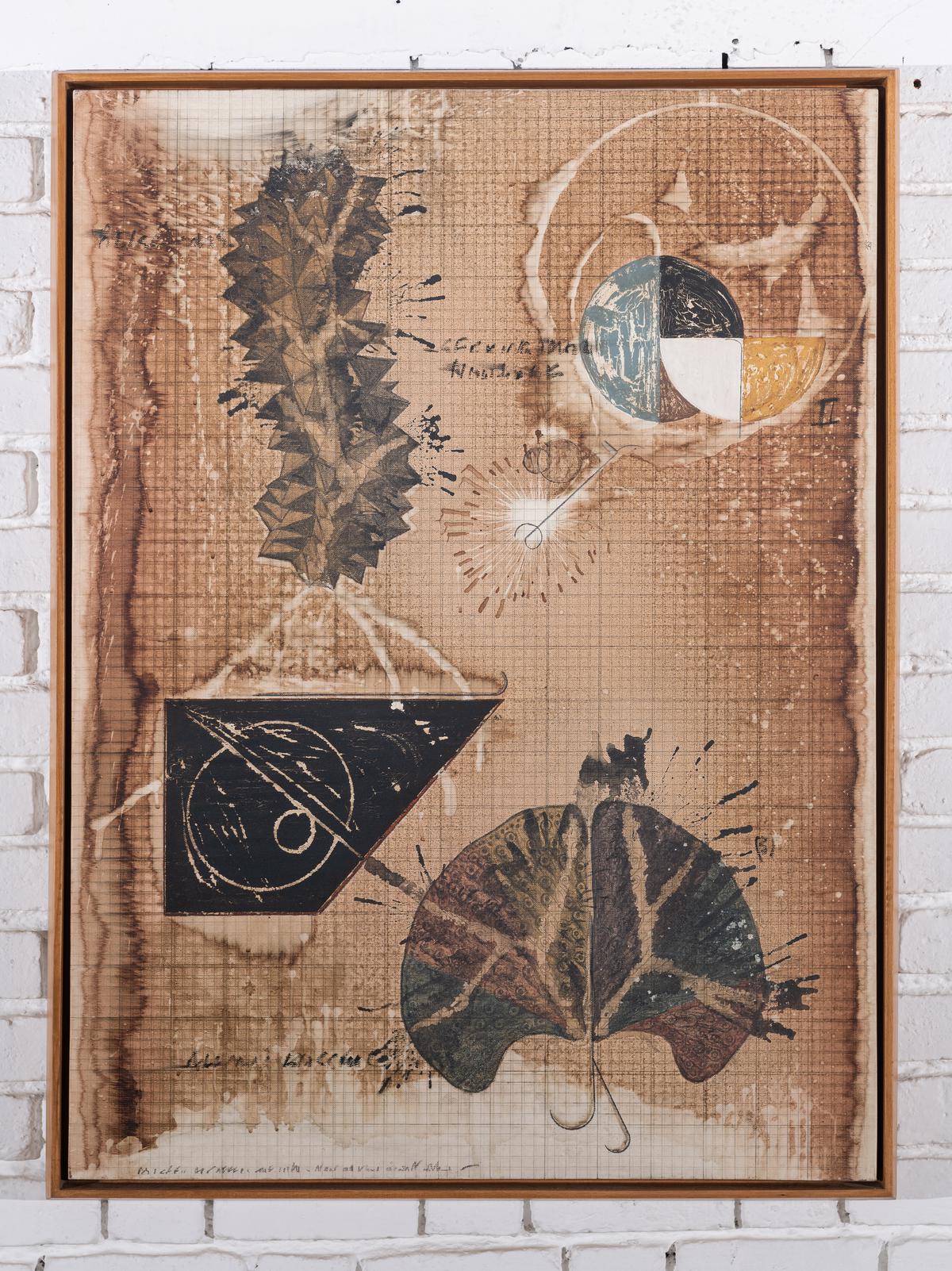

From Jitish’s series ‘Asymptote’

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

These conditions mean that sometimes the work has no expected outcome. He explains, “For me to experience at some level, the periphery and outer limits of my own perception, I might want to produce conditions in the studio.” In the past, he’s done works titled ‘Wind Study’ and ‘Rain Study’, both of which make use of the elements to record a particular moment in time, in this case using nature and the elements.

In ‘Echo Verse’, an eight-park work that is shaped like the Waterman butterfly, the grid that underlines the work is painted with water colours. He explains: “The graph itself will produce a kind of nebulous form, you know, that would become the starting point for the first image, and often the first image would almost produce the condition for the next image.” These are overlaid onto each other to make a work, that seems to map geological spectacles, through the controlled use of air and water to shape the pigments.

From the Integer Studies series

| Photo Credit:

Special Arrangement

Kallat says, “In the studio, there’s a peculiar sensation that one is witness to the same movement of matter that might happen on planet Earth.” Later, Kallat returns to this theme, saying, “I want to paint in a way that the painting meets you halfway with imagery that was just a moment before unforeseen,” mentioning how the way paint dries can mirror geological effects. He explains, “Something dries up in a certain way, it could become ferrous, iron-like, it dries up another way and it could become like earth, dries up in yet another way and it becomes completely fluid like silt, you know, and these are very subtle things.”

Notes on history

Tangled Hierarchy, a show curated by Jitish Kallat, will be shown at the Kochi Muziris Biennale. Having previously been shown in the UK, it is fitting that the work is also being shown in India, given that it centres on five envelopes on which Mahatma Gandhi wrote to Lord Mountbatten in June 1947.

The written communication was necessary as Gandhi had taken a vow of silence that day. Kallat explains, “But from that envelope opens up a conversation … the weeks that followed the writing of that letter,” and as a result, the installation which features artists like Zarina, Sir Roger Penrose, Kader Attia and Paul Pfeiffer among others is one that explores displacement, causal loops and phantom pain.

Kallat’s work has always been intent on collapsing the distance between himself and the cosmos, and this exhibiton is no different. Coming back to the Integer Studies, he notes about the three daily figures he’d note down, “It still ends up in an outward concentric way from the self, the rest of the planet.” Given the large numbers noted daily, Kallat explains: “At a very existential fundamental level, you know, several trillions of cells have passed away in our bodies , while we began this conversation, right, and several more have been born. So, it is a persistent condition, even within ourselves, this birth, death, regeneration, and that remains like a consistent inquiry in that yearly process.”

Asked to look back on his time as an artist, Kallat says, “I mean, artworks at some levels are fossil records of your own thinking, you know. They tell you, not just what you were thinking, they also tell you, you were thinking. They mirror the situation or the person you are at a point in time.” In 2022, Kallat is once again wrestling.