In the evening of the first day of a summer festival, two elderly men were sat on a wooden platform by the roadside staring intently at something between them.

Japanese Prints and the World of Go, by William Pinckard and Akiko Kitagawa

195 pages

KISEIDO PUBLISHING COMPANY

The festival was in that pre-dusk lull like a deep inhale before the evening roars to life, and into this silence came a sudden, sharp little sound. Tak. One of the men winced, rubbed his chin and leaned forward with an air of resignation. Tak. Of course, they were playing go.

Both men were utterly entranced by the game, oblivious to time and everything around them, including the curious onlooker inching closer for a better view.

This was my first exposure to go, and it turns out the tableau of players rapt before a board is one of many themes that run like threads through centuries of visual art. In “Japanese Prints and the World of Go,” Akiko Kitagawa and William Pinckard explore these meme-like themes, mapping a cultural Venn diagram at the nexus of art, history and this subtle game that has a way of weaving itself into our narratives.

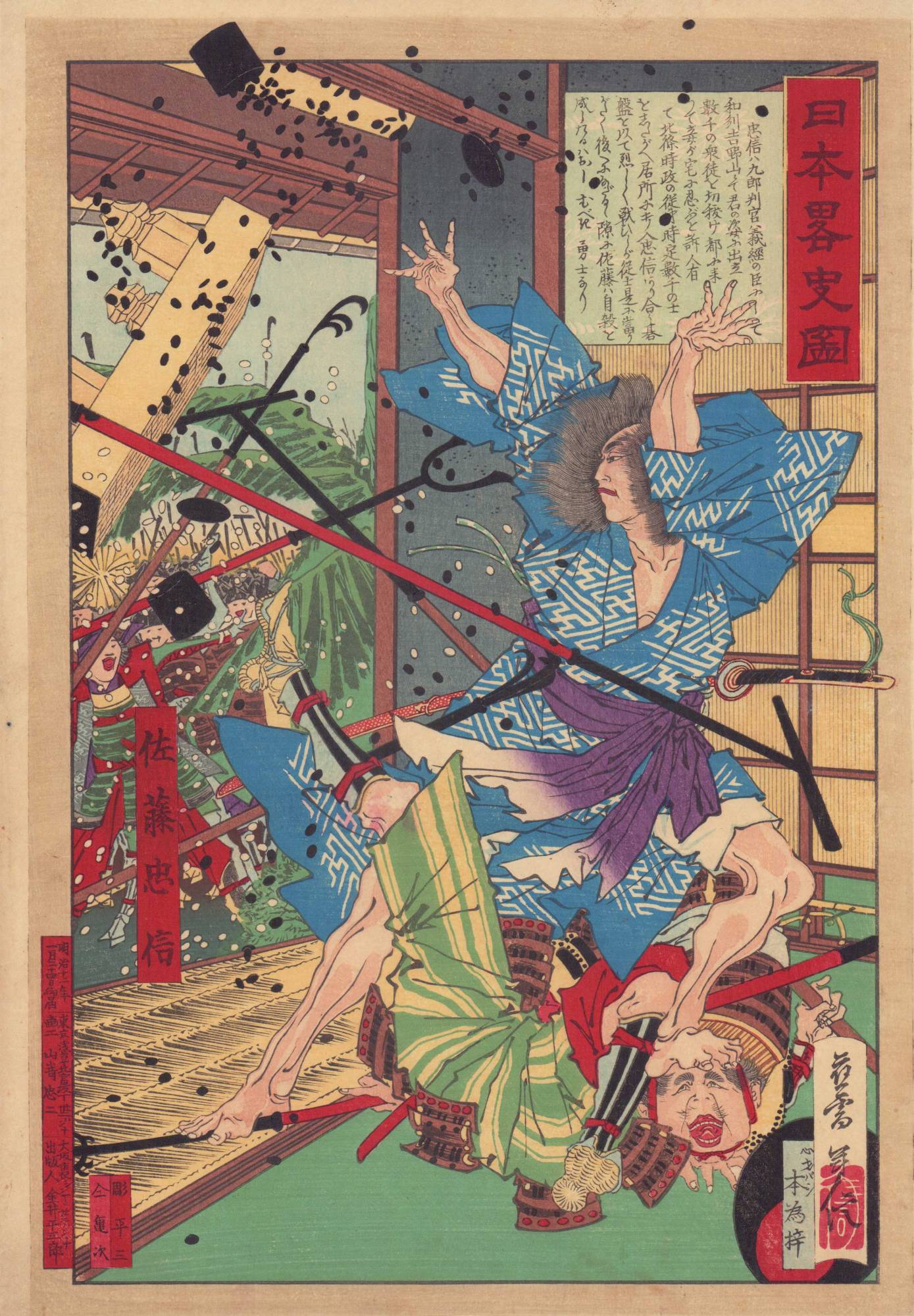

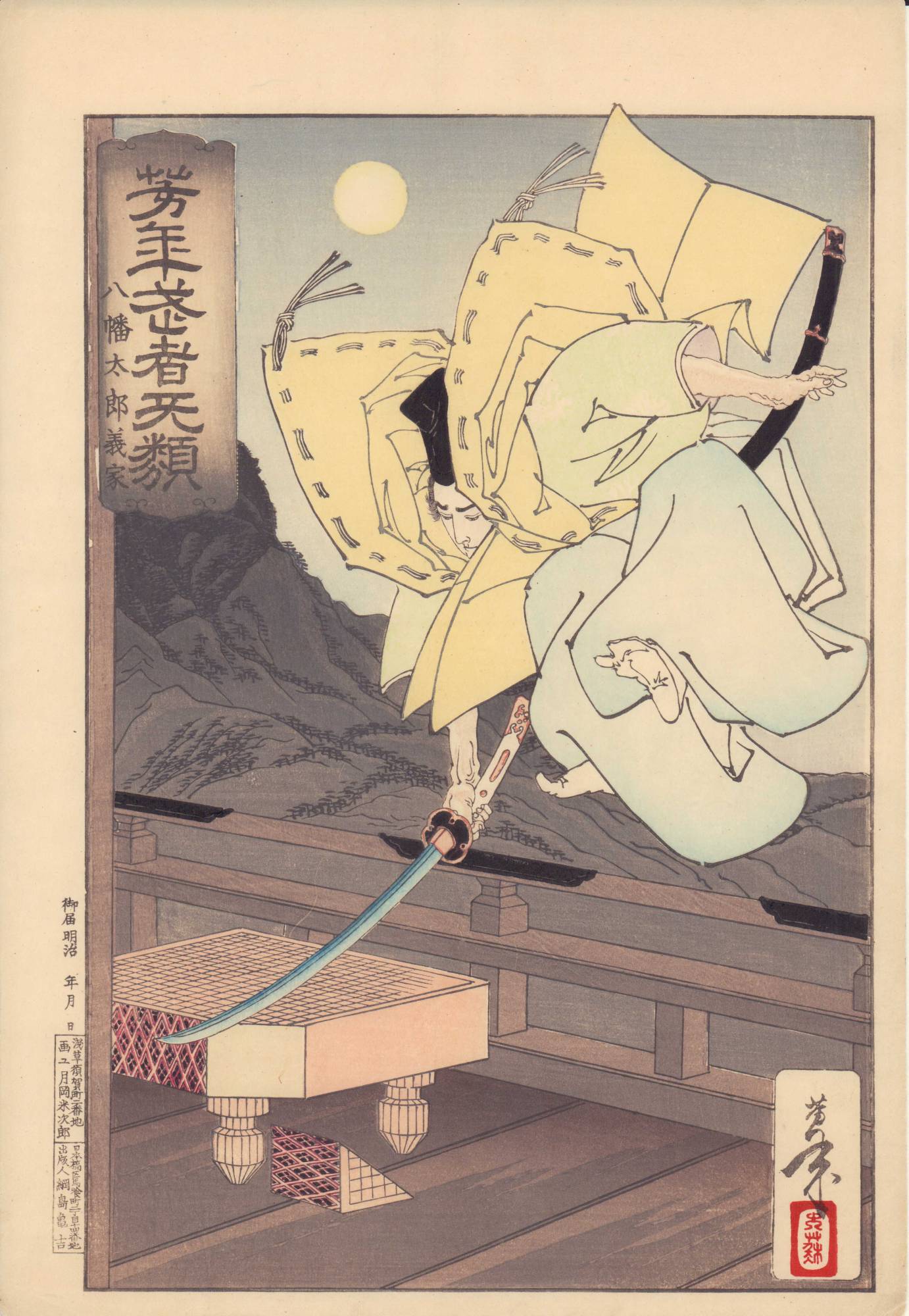

The result is a large, bilingual, softcover book that features 75 color plates from artists including Toyokuni I, Kunisada, Kuniyoshi, Utamaro, Yoshitoshi, Hokusai and others. In addition to curating the prints, Kitagawa fact-checked and corrected Pinckard’s essays on the go-related themes. She also turned her exhaustive research into commentaries on each print that shed light on go’s rich heritage as well as the pop-cultural psyche of people in the Edo Period (1603-1868).Two decades in the making, the book began in the mind of Pinckard, a devotee of go and a collector of ukiyo-e prints. Shortly before passing away in 1989, Pinckard gave 10 draft essays and his go-related prints to a friend, asking that they be published. That friend was author Richard Bozulich, now president of Kiseido, a publisher and purveyor of all things go. Bozulich enlisted the help of Kitagawa, who took up Pinckard’s baton to run a 10-year marathon of research and writing that ended with publication in 2010.

Good optics

It has to be said: A book that surveys instances of a board game appearing in a feudal art genre is niche indeed. Yet when viewed through the twin lenses of go and ukiyo-e, Edo Period Japan comes alive in surprising detail.

Go, for its part, has entranced people for something like 4,000 years. In more recent times, it inspired the invention of the QR code. And in 2016, a go board was the scene of a major turning point in the development of artificial intelligence (AI) when Google Deepmind’s AlphaGo became the first AI to beat a top-ranked human player.

According to Kitagawa, the story of go’s beginning is lost to time, though it is thought to have been connected with divination and the origins of the calendar. The game seems to have accompanied the transmission of Buddhism from China to Japan in the sixth century, where it took hold among the clergy before spreading to other classes, eventually enjoying a long, steady cultural ascendency. By the Edo Period, shogunate patronage was propelling it both to new depths of complexity and new heights of popularity, which is where the prints make their entrance.

Ukiyo-e was a major source of entertainment in its day, and much of the delight stemmed from the pouring of novel content into familiar vessels, a point Pinckard touches on in his preface.

“Most artists therefore worked in set forms and drew upon a limited and widely shared repertoire of subjects,” he writes. “Woodblock prints of the ukiyo-e school drew upon a deep pool of associations and allusions to which literature, legend, philosophy, and history each contributed, providing the public for whom they were made with an emotional resonance that went far beyond their purely graphic qualities.” In other words, ukiyo-e prints provide a window onto the lives of the people of that time.

The go-related prints in this volume are collected under themes such as “Prince Genji,” “Raiko and the Ground Spider” and “Go Board Tadanobu,” a Heian Period (794-1185) warrior who was often portrayed in plays fighting his way out of a besieged house with a go board.

There is also “The Immortals,” a theme that begins with a Chinese story in which a woodcutter encounters two Daoist immortals playing go deep in the mountains. Transfixed by their game, he wakes to find his ax handle has rotted and his beard has grown long — a comment on go’s hypnotic effect. But perhaps the most interesting are the 29 prints collected under “Scenes of Daily Life,” for the fascinating cross-section of quotidian affairs they present.

“During the Edo period a go club, like a tea ceremony room or a kyōka poetry meeting, was a place where rank, station and sex were irrelevant,” write Kitagawa and Pinckard. “What mattered were the depth of commitment and the skill of the participants. People who came to such clubs came as near to forming a genuine meritocracy as was possible in class-conscious Japan in those days, and this must have been a large part of the appeal of go for new players.”

Thanks to the universal appeal of go, “Japanese Prints” offers stunning depictions of courtesans and actors, warriors and famous beauties. It also illuminates the cultural milieu such people inhabited and the stories and myths they valued — all brought into focus by Kitagawa’s concise commentary.

A promise kept

Speaking to The Japan Times, Kitagawa and Bozulich look back on the difficult but rewarding process of making the book. Kitagawa recalls the odyssey of research that began at her city library, escalated through two prefectural ones and several others, and ended at the National Diet Library: “As I continued, it seemed that the amount of work necessary to complete it grew to greater heights. It was like climbing a mountain whose summit was invisible.”

Deciphering the ancient Japanese script on many of the images was a particular challenge, she says. “It was a gruelling job, but it was an invaluable experience and I am happy that I did it. Because Mr. Bozulich did not set a time limit and wanted absolute accuracy, I was able to do the book at my own pace.”

“I felt that publishing this book was something that had to be done,” Bozulich says of the final product. “I felt I had fulfilled my promise to Pinckard and had contributed something necessary and important to how go and the other cultural traditions of Japan are interwoven.”

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

SUBSCRIBE NOW