Visitors to Halifax would be forgiven for puzzling over the quirky routes of some of the city’s main thoroughfares.

For Haligonians, navigating the sudden road terminations and traffic bottlenecks has become a routine frustration during the daily commute.

The peninsula’s peculiar road layout was not the result of creative urban planning, but of a massive and disruptive engineering project from over a century ago.

Historian Bob Chaulk says the construction of the Halifax rail cut was such a transformational moment in the city’s history, he decided to explore its story more fully. His recent book Railroaded: The Untold History of Halifax’s Rail Cut chronicles the project’s turbulent history.

“The cut that goes right across the peninsula, which all people in Halifax know about because there are 15 bridges that they need to drive over … has not mangled the movement of traffic. But it messed it up,” he said.

The rail cut was a trench blasted across the peninsula to connect trains to a new ocean terminal, reshaping the city’s orderly street grid to a tangle of cutoff roads.

It explains such peculiarities as Connaught Avenue’s abrupt termination at Jubilee Road and Robie Street’s petering out at a wooded area.

The rail cut was born from a challenging time in the history of Halifax.

Founded as a British naval base in 1749, the city faced an uncertain future when the Royal Navy announced its withdrawal in 1904.

The military presence had been the economic engine of the city.

By 1907, the Royal Naval Dockyard was officially transferred to the government of Canada.

Halifax’s peculiar road layout is not because of confused urban planners, but the result of a massive and disruptive engineering project from a century ago. That’s when a new rail line was put in from one end of the peninsula to the other. The CBC’s Vernon Ramesar reports.

“The whole reason for the existence of Halifax ceased, basically,” Chaulk said.

“The logical thing to do was to become a commercial harbour. And that meant a huge amount of investment in both rail infrastructure and wharfs and docks.”

The Board of Trade’s solution was to reshape Halifax as a major commercial port.

This required a direct rail line to new deepwater docks bypassing the old, inefficient route that ended near Duffus Street, far from the piers.

According to Chaulk, it cost more money to transfer goods from the rail terminal to downtown than it cost for them to cross the Atlantic.

In 1912, plans were drawn to build a new integrated port and railway system on the peninsula. At the time it was the largest project in the British Empire.

Chaulk said the federal government decided the location and mapping of the cut without conferring with the city. The mammoth project that followed carved through neighbourhoods with little to no local consultation.

The 10-kilometre cut from the South End to Fairview Cove required the blasting and removal of more than two million cubic metres of rock.

The First World War compounded the challenges, causing labour shortages and logistical conflicts.

For residents of the South End, particularly those along Young Avenue and Tower Road, the construction was a four-year ordeal.

They endured near-constant blasting, dust, and disruption for 24 hours a day, six days a week.

“This whole project was done before there was anything on rubber tires,” Chaulk said.

“There were no excavators, there were no bulldozers, there were no graders, no backhoes. Nothing but a steam shovel and … literally a worker with a shovel.”

Rock that was removed to create the cut was transported on a temporary rail line to the harbour and used to construct the new pier, called Pier A, near what is now Pier 21.

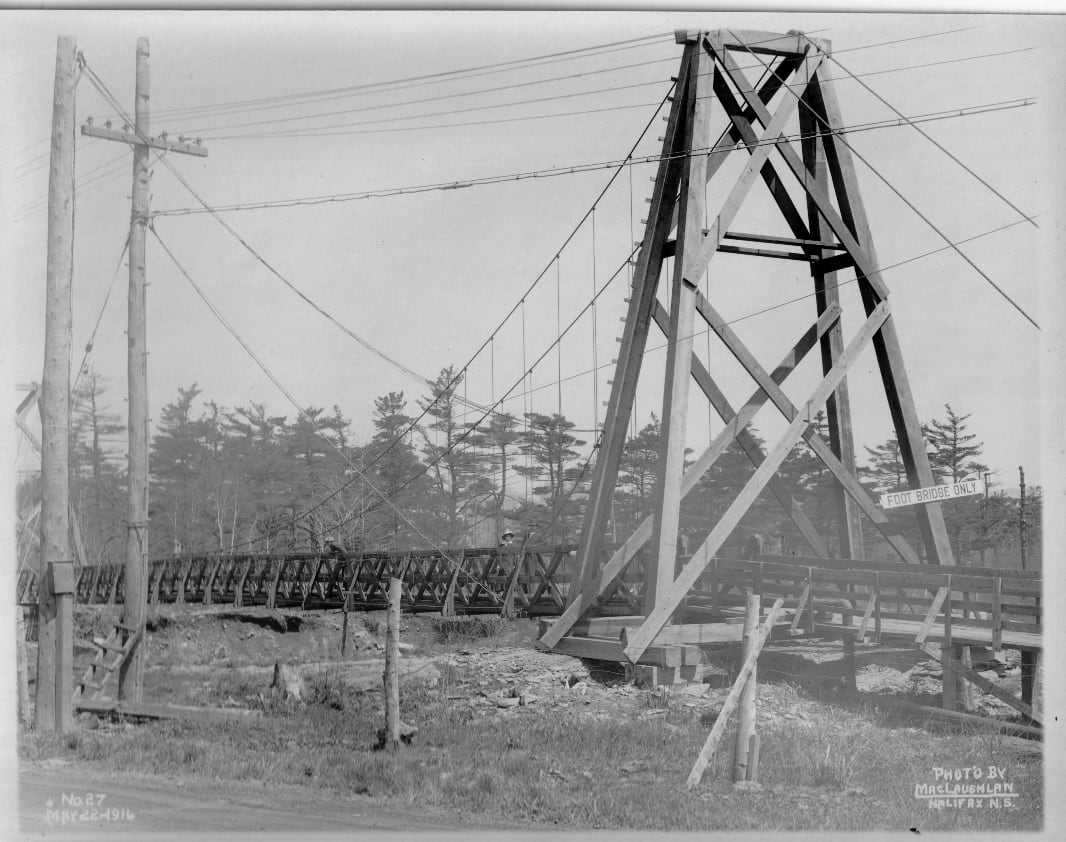

As the trench advanced, detours grew longer until a temporary footbridge was installed at Young Avenue to connect those on the other side of the trench to the rest of the community. Fire, water and sewer services to those residents were also disrupted.

A permanent bridge was completed in early 1918.

The importance of the project was made starkly clear after the Halifax Explosion on Dec. 6, 1917.

The blast destroyed the existing railway terminus in the North End.

The new cut, though not fully complete, became an crucial artery for relief supplies.

“Within just a day and a half, the relief trains were coming in here because otherwise they were stuck out in Rockingham,” Chaulk said.

The cut ultimately succeeded in its goal, forging a direct rail link to a modern port, but it permanently altered the city.

More than a hundred years later, the city continues to manage the cut’s infrastructure. The aging bridges require costly maintenance and replacements.

Much of the land adjacent to the trench is underutilized and truck traffic to and from the port is a major contributor to congestion in the downtown area.

Chaulk said it’s the lasting, but underrecognized impact of the rail cut on modern Halifax that compelled him to write its story.

“Now that I’ve done all the research and written the book, I really can’t understand why this story has never been told because it’s actually a pivotal point in the history of the city.”

MORE TOP STORIES