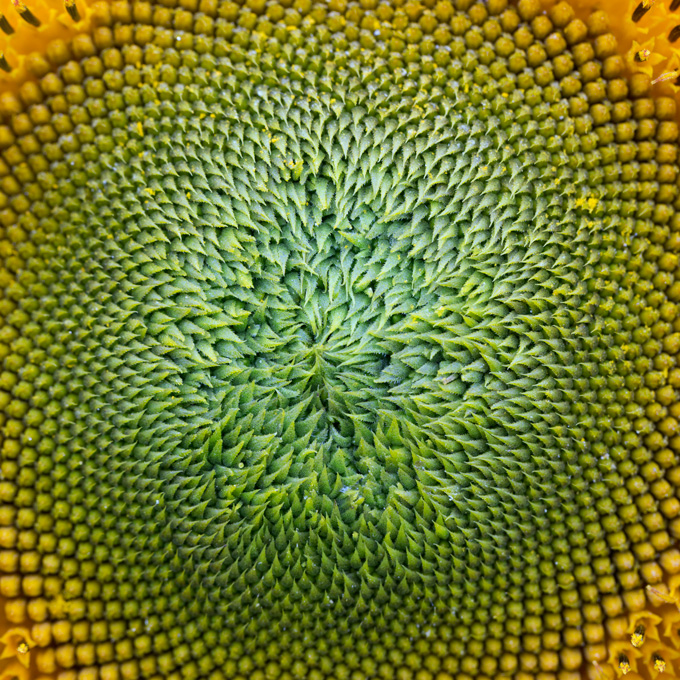

Mosaics can enchant humans with gestalt beauty, but for many other creatures, their worth transcends aesthetics. Repeating patterns of tilelike motifs adorn insect eyes, shark mouths, sunflower heads and many other organisms, providing a diverse array of benefits, researchers report in the November PNAS Nexus.

“These surface designs exist on literally all scales,” says biologist John Nyakatura of the Humboldt University of Berlin. “This is not something that is restricted to just a single lineage, or just a few lineages in biology,” he says. “It’s a solution that evolution found many times independently.”

Nyakatura and his colleagues were keen to learn how tiled surfaces could be leveraged in bioinspired devices. Turning to nature for insights, the researchers focused on organism surfaces patterned with repeating units separated by a connective material — think tiles and grout. They called these natural motifs “biological tilings” and cataloged 100 examples gathered from websites, social media and discussions with scientists.

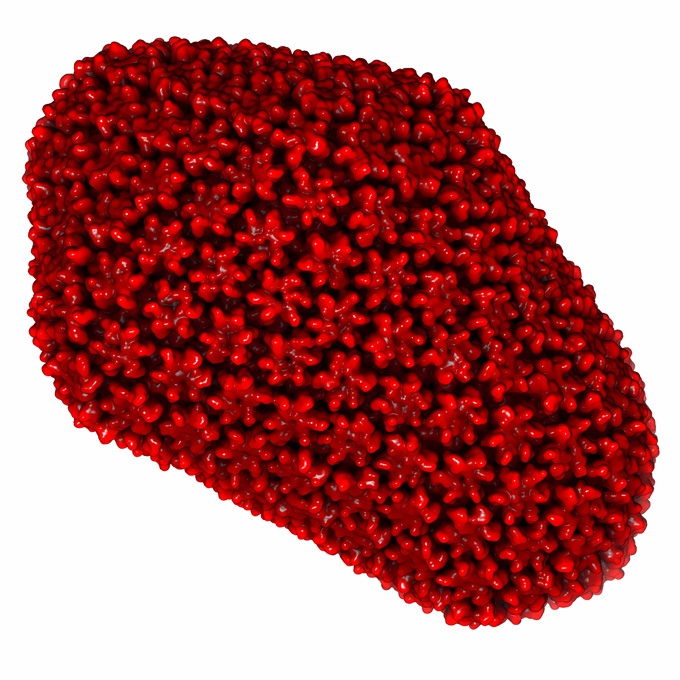

The catalog spanned an astounding range of tile sizes, from several-nanometers-wide capsomeres in virus protein shells to tens-of-centimeters-wide plates of giant turtle shells. Tiles ornament a wide breadth of organisms as well, including plants, arthropods, mammals, fish, tardigrades and mollusks.

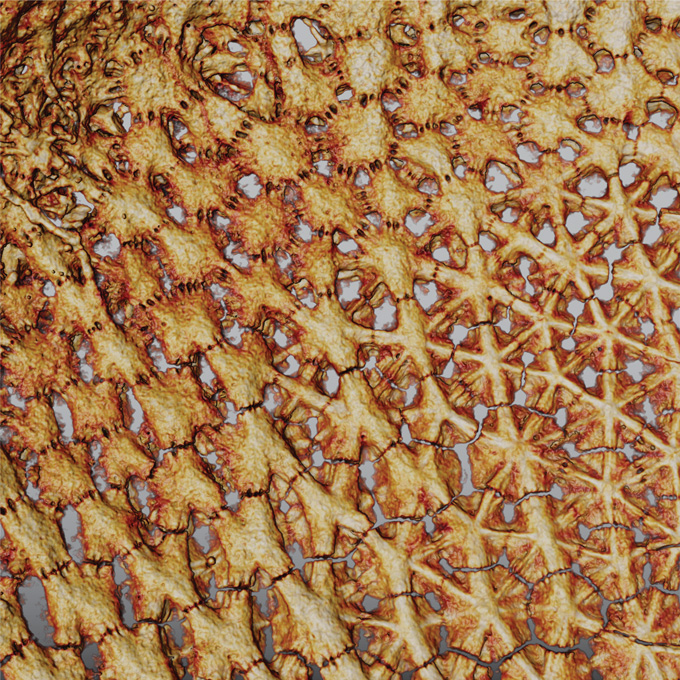

What’s more, tilings serve a variety of functions, from capturing light in compound insect eyes to protecting the skeletons of sharks. And in many cases, they serve multiple functions. For instance, tessellated elephant skins possess networks of cracks that retain water and mud, helping to both regulate body temperature and shield against parasites and solar radiation.

But most often, Nyakatura says, tiled surfaces provided protection while still allowing for some flexibility. “If it’s just a solid surface, then maybe movement would be restricted or not be controlled in the way that we, for example, see in armadillos,” he says. They “can roll almost into a ball in one direction, but in other directions are pretty stiff.”

By studying the geometries and benefits bestowed by these natural tiles, designers might be able to improve the surfaces of many products. Knee pads that adapt to growing children and building facades with improved cooling are just a couple of examples, Nyakatura says. “It can be anything.”