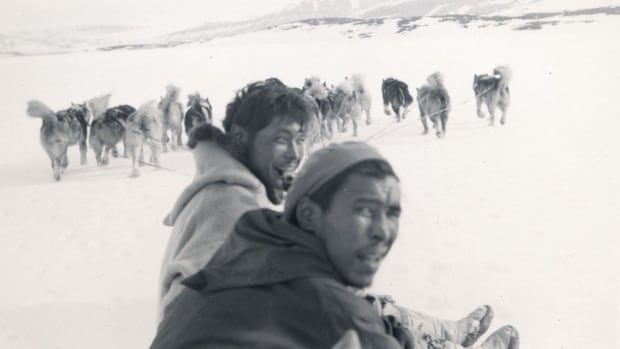

Getting the Canadian government to apologize for its role in the mass killing of Nunavik sled dogs has been a 25-year-long mission for Pita Aatami, the president of Makivvik Corporation, which represents Inuit in Nunavik.

For him, Saturday night’s apology inside a crowded community centre in Kangiqsujuaq, Que., was a step toward closure.

“It hurt not just the person that lost the dogs, but the whole family. They had no more means of going out on the land to go hunting, fishing, get ice and pick up driftwood,” he said.

To this day, Aatami said he still hears new painful stories about the dog slaughter, a period in the 1950s and 1960s when police officers and other authorities killed over 1,000 qimmiit [sled dogs] in Nunavik, the Inuit region of northern Quebec.

One of the stories that haunts him is from Louisa Cookie of Kuujjuarapik, who spoke about trying to protect her dogs.

“She almost got shot herself twice trying to protect the dog … the police had no regard for the human part … that people were pleading ‘please don’t kill our dogs, that’s our only means of surviving here’,” he recalled.

Gary Anandasangaree, the minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations, acknowledged during the formal apology that it should have come sooner.

“Because we waited, many whose lives were affected by the dog slaughter are not with us to hear this apology,” he said.

“While apologies and acknowledgements will not bring back what you lost, I hope it gives you some confidence that we can move forward together. I hope it gives you some closure.”

Along with the formal apology, the federal government will give Makivvik Corporation $45 million in compensation for Inuit in the region. Part of the money, Aatami said, will go towards revitalizing the culture of dog team ownership, which includes training, food, and fencing. Some is also expected to go towards direct compensation for those impacted.

‘Inuit had to have dogs’

Anandasangaree met with Nunavik elders to hear their testimony about the dog slaughter ahead of the formal apology. Speaking to CBC after the ceremony, he said he had heard many stories about the dog slaughter in Nunavik he hadn’t previously known.

They include the fact that some dogs were killed by carbon monoxide poisoning, as well how Inuit used dogs beyond just transportation, including in identifying seals.

“The number of women who spoke, who themselves were leading dog teams, was also very powerful,” he said.

Despite all those losses, Inuit in Nunavik have fought to keep their traditions alive.

Since 2001, mushers in the region have competed in the annual Ivakkak Race, a multi-day event which traverses hundreds of kilometres through various communities.

Junior May, Kuujjaaq resident and self-proclaimed dog lover, won the race in 2002.

“I learned from my dad and some elders. Like qamutiik [sled] making… I make all my own harnesses. So you learn a lot that an average Inuk that is not dog teaming doesn’t know,” he said.

Before the 1950s and 1960s, dog sleds were the only mode of transportation during winter, he said, with no snowmobiles or contact with the south.

“Inuit had to have dogs. And if they didn’t, it was known that they were almost starving because you can only walk so far,” he said.

For many years, May said, elders didn’t really speak about the pain of the slaughters. Knowing that their pain has finally been acknowledged by the federal government makes him happy, especially for those like his grandparents who lived through the dog killings.

More to do in path towards reconciliation

A 2010 report from Jean-Jacques Croteau, a retired Superior Court of Quebec judge, found Quebec provincial police officers killed more than 1,000 dogs “without any consideration for their importance to Inuit families.”

The federal government’s role in it, Croteau found, was failing to intervene or condemn the actions.

The events of the dog slaughter were linked to residential schools, he found. The schools forced many families to upend their lives and settle in communities close to those schools, bringing their dogs with them.

Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Gary Anandasangaree has formally apologized to Inuit in Nunavik for the federal government’s role in the mass killing of sled dogs in the region in the 1950s and 1960s.

Historically, Inuit didn’t tie their dogs, Aatami said, as they needed constant exercise to stay healthy enough to pull sleds.

Law enforcement would kill any dogs that came loose. Croteau’s report found some white people would even untie dogs purposely.

“The dog issue was handled as though it were a highway safety offense or a municipal by-law violation,” he wrote.

The Quebec government formally apologized to Nunavik Inuit a year after that report.

RCMP representatives were present during the federal apology on Saturday.

While the RCMP handed over law enforcement in Nunavik to the provincial police service, the Sûreté du Québec, in 1961, RCMP officials said it was important for them to show up for the apology.

Rouben Khatchadourian, the RCMP’s assistant deputy minister of strategic policy, communications and external relations, said he cannot rewrite the past, but he is optimistic this apology can bring some hope and closure.

“If our presence here, our contribution, helped toward that path … then that is why we wanted to be here,” he said.

Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national body representing Inuit, said this apology is just one step towards reconciliation amongst the “intricate web of colonization” that still impacts Inuit today.

“I think there are much larger reconciliation funds that are necessary, whether it be Inuktut infrastructure, housing, tuberculosis elimination, we know there’s a lot more money needed for our equity as Inuit with the rest of the country,” he said.