Brothers locked in rooms for 18 hours, restrained with zip ties overnight, co-accused tells Ont. murder trial

WARNING: This story details allegations of child abuse.

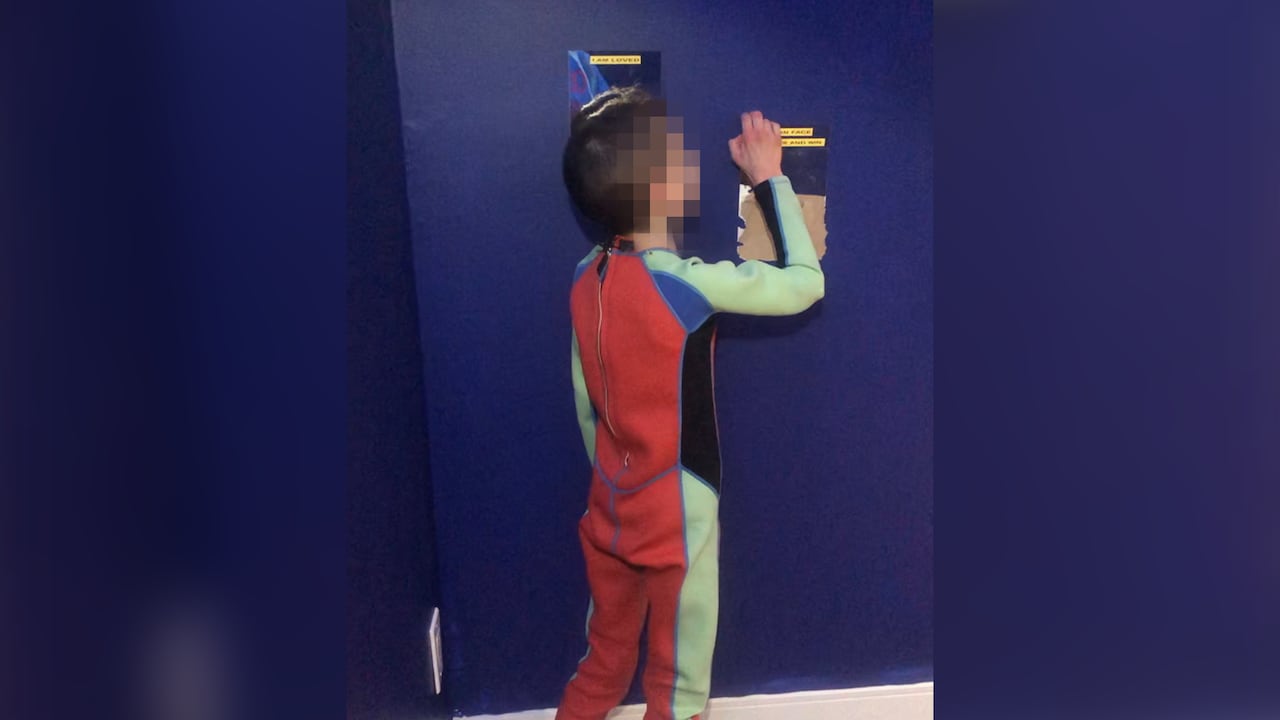

In the last year a boy in Brandy Cooney’s and Becky Hamber’s care was alive, he and his brother were locked in their bedrooms for 18 hours, zip-tied into wetsuits, tube-like sleep sacks and hockey helmets, and surveilled on cameras, a Milton, Ont., court was told during Cooney’s second day of testimony.

Cooney underwent intense cross-examination Tuesday by assistant Crown attorney Monica MacKenzie.

The Crown challenged Cooney’s narrative from the day before, when she said she and her wife loved and cared for the boys and rarely used restraints, even though she claimed the brothers injured her and her wife, destroyed their Burlington home, urinated and defecated everywhere, and had unpredictable, explosive tantrums.

Cooney and Hamber are charged with first-degree murder of the 12-year-old, as well as confinement, assault with a weapon — zip ties — and failing to provide the necessaries of life to his younger brother.

Both women have pleaded not guilty.

(Ontario Superior Court in Milton)

CBC Hamilton is referring to the older boy as L.L. and his brother as J.L. as their identities are protected under a publication ban. The Indigenous brothers were in Cooney’s and Hamber’s care from 2017 until L.L. died in their Burlington home on Dec. 21, 2022.

At death, L.L. was severely malnourished and weighed the same when he was six years old, the court has heard during the trial, which began in mid-September.

Cooney’s account of what methods she and Hamber used to control the boys changed from Monday, when asked questions by the defence.

Cooney had said she “never” used restraints on J.L., except when she held him for seven hours, comforting him.

But when questioned by the Crown and Justice Clayton Conlan on Tuesday, Cooney said they restrained both boys for their own protection.

“Yes I did use a jacket, so he didn’t try to choke himself and die,” she said. “And yes, I did zip-tie the end of [their wetsuit] sleeves to stop them from using their hands to choke themselves out.”

Cameras, bells, chimes used to monitor boys

Most nights in 2021 and 2022, the boys would be zip-tied into wetsuits or sleep sacks, Cooney said.

Bells were strung across J.L.’s bed so the women knew when he moved at night, she said. Along with cameras in nearly every room — the videos of which the women watched on their phone much of the day — they suspended chimes above doors to alert them to where the boys were in the house.

Cooney said they’d also sometimes zip-tie helmets on the boys’ heads to prevent them from punching themselves.

“Restraints were a last resort,” she said. “A lot of times, I’d sing with them, try to talk them through things and hand them a journal. Sometimes you could redirect their behaviour by giving them a solid hug, sometimes a snack.”

But after further questioning from MacKenzie, Cooney agreed the boys were “at times” restrained often.

Over the years, the women had described the boys’ self-harming behaviour and what they called uncontrollable “tantrums” to the Children’s Aid Society (CAS), therapists, doctors and teachers, but these behaviours were rarely, if ever, observed by anyone else.

The Crown pulled, from 8,000 pages of text messages between Hamber and Cooney, examples of what the women considered bad behaviour.

In 2019, Cooney texted that L.L. got home from school and took off his jacket and splash pants, which appeared to make her angry. She wrote to Hamber he was a “useless pee baby” and Hamber responded “he needs spanking.”

Other examples that prompted the women to text insults about the boys included when one or both were sitting too far from the table, eating too fast, dancing in their room and “trashing” their bed.

In 2020, one boy said to Cooney, “Love you more than just saying it.” She texted Hamber she considered it “talkback.” Hamber told her to ignore him.

Long periods locked in rooms

The boys, who were kept home from school beginning in 2020, were sent to their rooms after dinner around 6 p.m. to “decompress,” Cooney said. They’d go to sleep a few hours later and she’d wake them up in the middle of the night to use the washroom.

As documented in text messages from 2021 and 2022, Hamber or Cooney would let the boys out of their locked rooms around noon. In the meantime, they had “activities” to complete, including burpees, sitting against a wall, walking laps or reading, Cooney said.

MacKenzie said this meant the boys had one chance to go to the washroom over about 18 hours — which Cooney denied, claiming Hamber let them use it when they first woke up around 9 a.m., although there’s no evidence indicating this happened.

The court previously heard that the women would scold L.L. for “peeing and pooping himself” and say he was “choosing” to do so in a misguided attempt to get what he wanted. J.L. has testified he’d sometimes pee himself in his bedroom because he couldn’t hold it any longer.

Boys broke toys, plates, co-accused says

The defence has argued throughout the judge-alone trial that the boys caused extensive property damage totalling tens of thousands of dollars. Cooney and Hamber had told CAS workers and therapists the same.

But on Tuesday, Cooney could only recall smaller issues, like their screen door was dented, the freezer was no longer sealed properly, a corner broke off their glass table and pee was found under a cat tree.

Four mattresses were ruined when the boys peed on them, she said. The boys’ clothes would have holes and rips in them, and they’d break cups, plates and toys.

“Is there anything else?” asked the judge. “There is other evidence [in this trial] that led me to think there was complete destruction of the house, annihilation, worth thousands and thousands and thousands of dollars.”

In response, Cooney said that one time, J.L. had “ripped” a coat rack off his bedroom wall, creating four holes, and L.L. had “smashed” his closet door.

Why co-accused didn’t seek medical treatment

Cooney and Hamber also told people the boys had injured both women, the court has heard.

But Cooney said on Tuesday that they never sought medical treatment, including for J.L.’s or L.L.’s apparent self-harm. The only exception, Cooney said, was when L.L. “punched” Hamber in the face, causing her to fall and fracture her arm. Hamber went to a walk-in clinic and got a sling, but not a cast because she was allergic to them.

They had no documentation of this visit, Cooney said.

“The reasons for restraints and locking them in their rooms was because you were so worried about injury to you or Hamber, or the boys or pets — injuries which never happened?” said MacKenzie.

“There were a lot of injuries over the years,” Cooney said. “We were often hit, punched, kicked, stuff thrown at us.”

“But not to the extent that you had to seek medical attention?” asked MacKenzie.

“No,” said Cooney.

The trial continues today.

If you’re affected by this report, you can look for mental health support through resources in your province or territory.