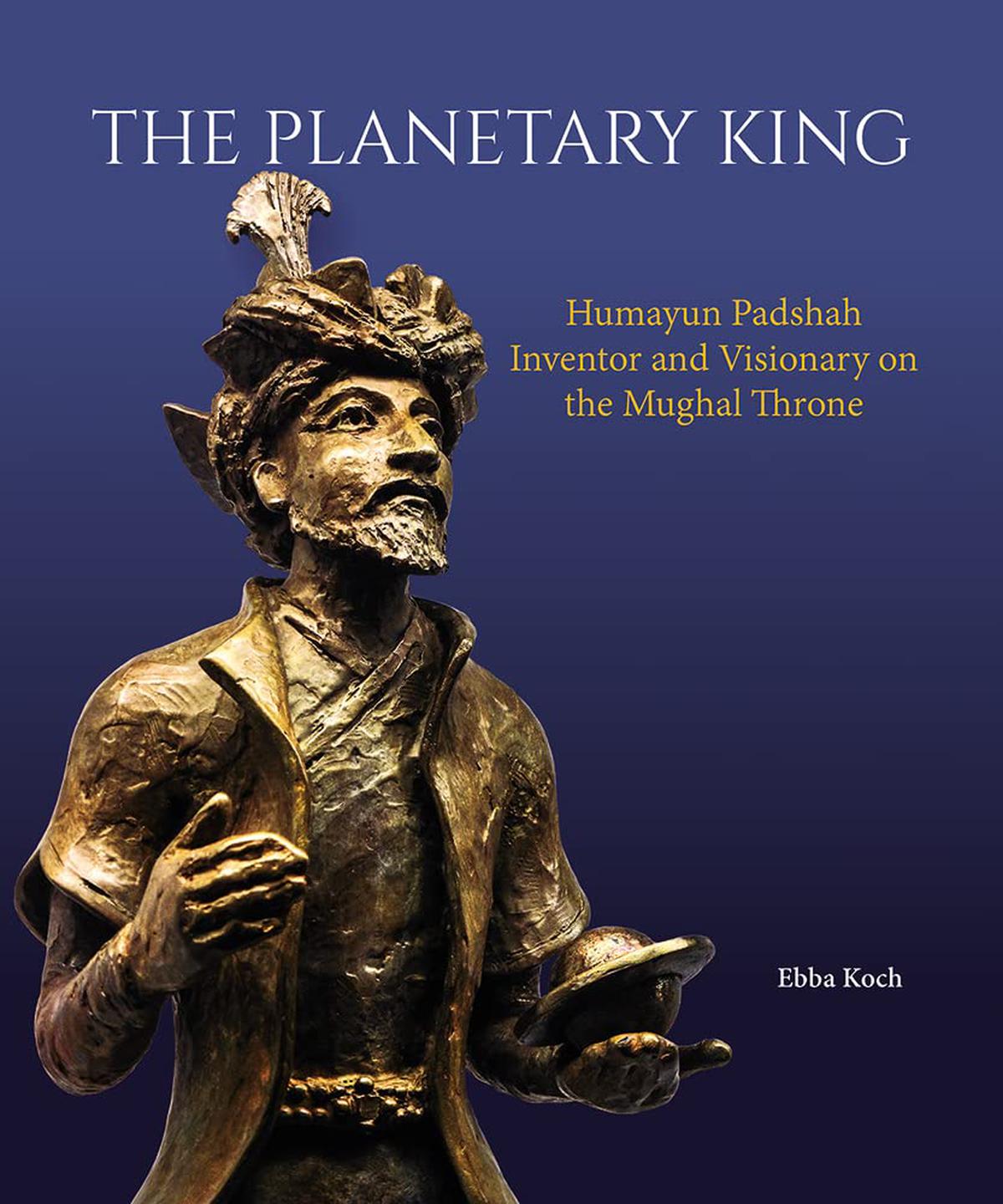

Austrian historian Ebba Koch spotlights the forgotten Mughal emperor Humayun in her new book The Planetary King

A miniature of Emperor Humayun by 17th century painter, Payag.

Neither mourned, nor remembered by millions, Humayun is almost the forgotten Mughal emperor. Sandwiched between Babur, the founder of the Mughal dynasty, and Akbar, the greatest Mughal emperor, Humayun cuts a forlorn figure. Deeply interested in astronomy and astrology, he was a man of many oddities, and deserves more than the cursory attention that has been his fate in school textbooks.

Ebba Koch

Shining the light on him now is Austrian art and architecture historian Ebba Koch who has taught at Oxford and Harvard, and in 2016, became advisor to the Aga Khan Trust for Culture (AKTC).

Her book The Planetary King: Humayun Padshah, Inventor and Visionary on the Mughal Throne (Mapin Publishing and AKTC) was launched in New Delhi on the emperor’s birth anniversary on March 6. Koch describes Humayun as a man remembered more for his failures than successes. He proved to be a comeback man, however, winning back the kingdom he lost, and there is certainly more to him than what is known in the public domain, said Koch at the book’s release. Edited excerpts:

Babur is remembered for his gardens, Jahangir for miniature paintings, Shah Jahan for the Taj. What about Humayun? Is he the forgotten Mughal?

Indeed. Humayun is chiefly remembered as a political and military failure because he lost to his rival Sher Shah Suri what Babur had conquered in India, had to seek refuge in Iran and fight in Afghanistan to regain his throne in Delhi. He did not write his autobiography and what his historian Khwandamir recorded ( Qanun-i Humayuni) is so eccentric that it eludes general comprehension. Abu’l Fazl glorifies Humayun as the father of Akbar but then he fades increasingly from historical memory and is best known through his splendid tomb, erected by Akbar in Delhi. In the book, I try to take the view away from previous approaches to Humayun to form a more holistic picture of the second Mughal padshah to restore him to the place he should rightfully occupy in Mughal history.

The period from 1530 to 1556 is almost like a vacuum in time for students of history with Humayun being mentioned only fleetingly. How does one talk of a man who lost his empire yet managed to come back to power?

Humayun is not considered a great warrior even though historians have studied his battles and increasingly rehabilitated him as a general. But if we combine this aspect of the monarch with his intellectual persona, it implies enlarging the world of Timurid-Mughal princes and including Humayun within an extraordinary group of educated and gifted savants who were also diplomats, mathematicians, astronomers, astrologers and generals. Humayun did not conform to the established notions of kingship, he was a free thinker and broke social conventions. The originality of his thinking and his inventions made it difficult for future generations to understand him and thus they preferred to ignore Humayun.

Shah Jahan began the construction of his new capital from Shahjahanabad, and not from the tomb of his great grandfather. Will it be accurate to say Humayun had been overlooked by the Mughals themselves less than a century after he died?

Near Humayun’s Tomb was the Purana Qila, the palace fortress, and other Mughal buildings. Shah Jahan wanted to have his own capital according to his ideas and started its construction with a palace fortress, the Red Fort, opposite Salimgarh, which had been the residence of the Mughal emperors when they visited Delhi before Shahjahanabad. Interestingly, it was Shah Jahan who showed a new interest in Humayun. His court poet Abu Talib Kalim Kashani wrote a poem on Humayun’s tomb, and Shah Jahan saw the domed mausoleum as inspiration for the Taj Mahal. Shah Jahan also gave a new architectural expression to the solar cult of the Mughal emperors which had been initiated by Humayun’s planetary court.

The terrace of Humayun’s Tomb in Nizamuddin, New Delhi.

| Photo Credit:

Getty Images

Has there been a monarch in Indian history to rival Humayun’s love for astronomy and astrology?

I can’t think of any ruler with Humayun’s knowledge and interest in astronomy and astrology in Indian history. Humayun had the best scientists to advise him. The scholar Muslih al-Din al-Lari from Shiraz was at Humayun’s court in the 1530s; he wrote on cosmological concepts which would have been of interest to the padshah. A special favourite of Humayun’s was Maulana Nur al-Din Tarkhan from Jam in Khurasan, who was distinguished for his knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and the use of the astrolabe. Abu’l Fazl mentions the Hindu astronomer or astrologer Maulana Chand, who had ‘great skill in and knowledge of the astrolabe and the details of the star catalogues and casting horoscopes’. He was placed by the padshah in his wife-consort Hamida Begam’s entourage at Amarkot to cast the horoscope at Akbar’s birth.

Other scholars such as Shaikh Abu’l Qasim Astarabadi and Maulana Ilyas al-Ardabili, with whom Humayun studied astronomy and mathematics, joined his court in Kabul. Humayun himself wrote scientific treatises and is credited with a mathematical text for his son Akbar. Jahangir was proud to own a manuscript by his grandfather, which contained an ‘introduction to the science of astronomy and some other unusual matters, most of which he had experimented with, found to be true, and recorded therein’. When Humayun returned to India, he planned to construct an observatory.

Humayun gave us the Sabz Burj, Sheikh Quddus’s tomb (Saharanpur), the Sher Mandal. Yet, he is not given credit for these architectural marvels.

Nila Gumbad, located within the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Humayun’s Tomb complex.

| Photo Credit:

Wiki Commons

Sabz Burj and Nila Gumbad are not mentioned in the sources, but the mausoleum of Sheikh Quddus is said to have been built by Humayun and the tradition is kept alive by the descendants of the Sheikh. Sher Mandal can be identified by the library building at Purana Qila. Recording all the buildings commissioned by the Mughal emperor became a part of history only in Shah Jahan’s time.

Will Mughal history be complete without Humayun?

Humayun is the most intriguing and thought-provoking ruler of the dynasty and if we engage with his personality and ideas, it will shed a new light on the potential of these extraordinary rulers.

ziya.salam@thehindu.co.in