In 2013, Ning Zeng came across a very old, and ultimately very important, log.

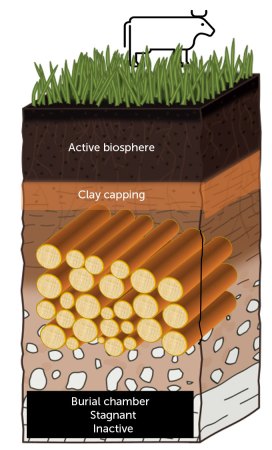

He and his colleagues were digging a trench in the Canadian province of Quebec, one that they planned to fill with 35 metric tons of wood, cover with clay soil, and let sit for nine years. The team hoped to show that the wood wouldn’t decompose, a proof-of-concept that burying biomass could be a cheap way to store climate-warming carbon. But during excavation, they unearthed a pristine, twisted log that was very old, older than anything they could have possibly produced in their experiment.

“I remember standing there just staring at it,” says Zeng, a climate scientist at the University of Maryland. He recalls thinking, “Wow, do we really need to continue our experiment? The evidence is already here, and better than we could do.”

That log was once part of an Eastern red cedar that drew carbon dioxide from the air and transformed it into wood some 3,775 years ago, researchers report September 24 in Science. Buried beneath as little as two meters of clay soil for millennia, the log retained at least 95 percent of that carbon, the study estimates.

“Scientists and entrepreneurs have long contemplated burying wood as a climate solution. This new work shows that it is possible,” says Daniel Sanchez, an environmental scientist at the University of California, Berkeley who wasn’t involved in the study. “High-durability, low-cost climate solutions like these hold immense promise for fighting climate change.”

New solutions are sorely needed. Curbing greenhouse gas emissions isn’t enough to meet global climate targets, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (SN:1/9/16). In addition, about 10 gigatons of atmospheric carbon needs to be captured and stored annually by 2060. Plants store about 220 gigatons of carbon dioxide each year just by growing, but much of this gets released back to the atmosphere through decomposition. Preventing just a fraction of that decomposition by burying wood could help meet this goal. But that potential rests on finding conditions that would prevent air, water and microbes from breaking down that carbon for long enough to make a difference.

The ancient log gives researchers a clue. Zeng suspects the largely impermeable clay soil blanketing the region helped prevent oxygen from reaching the log, even at relatively shallow depths. “This kind of soil is relatively widespread. You just have to dig a hole a few meters down, bury wood, and it can be preserved,” he says.

Burying wood could cost as little as $30 to $100 dollars per ton of CO2, the researchers estimate. That simplicity and cost, Zeng says, makes wood vaults more practical than developing direct air capture technology, which runs $100 to $300 per ton of CO2. If the conditions that preserved the Canadian log can be replicated — which is still unclear — buried biomass from discarded wood and sustainable harvesting could sequester up to 10 gigatons of carbon annually, the researchers estimate.

Despite finding the ancient log, Zeng’s team carried out their planned experiment and are wrapping up the analysis now, in part to figure out best practices. But the log itself exemplifies wood vaulting’s promise, he says. “We now have the evidence to say ‘yes, it’s ready to be implemented.’”