Whoever emerges from the upcoming Liberal leadership race will face a formidable Conservative challenger with a populist message and deep connections to Alberta. And this battle for the nation’s top political post has a distinctly western Canadian flavour, with three major figures tied to the region.

On Friday, CBC News reported former Bank of Canada governor Mark Carney is expected to formally announce his bid to replace Prime Minister Justin Trudeau late next week, backed by more than 30 MPs.

Carney is seen as an outsider who could offer a fresh start for the party. While his name may evoke images of central banks and monetary policy, Carney’s roots tell a lesser-known story.

Raised in Edmonton, Carney went to high school in the city before embarking on a career in finance. His Alberta upbringing has long fuelled speculation he might seek a seat in Edmonton.

Former finance minister Chrystia Freeland also has Alberta roots. She was born in the picturesque small town of Peace River, Alta. Her father was a lawyer and farmer, while her Ukrainian mother ran for the federal NDP in Edmonton during the 1988 federal election.

Then there’s Christy Clark, who made her political mark in the West as a British Columbia premier — though her leadership ambitions are now being overshadowed by questions about previous membership in the federal Conservative Party.

Former B.C. premier Christy Clark tells CBC’s The House that she is seriously thinking about running to replace Justin Trudeau, but she’s disappointed in the leadership race’s short timeline.

“The centre of politics has changed,” said Ian Brodie, who was chief of staff to Stephen Harper when he was prime minister, on this week’s West of Centre podcast with host Kathleen Petty.

“The centre of the country’s economy has changed,” he said. “The centre of the creative part of the country has shifted. The seats in the House of Commons have shifted west.”

Only two candidates so far have thrown their hats into the ring to succeed Trudeau — Liberal backbencher Chandra Arya from Ontario, and businessman Frank Baylis, a former Québec MP.

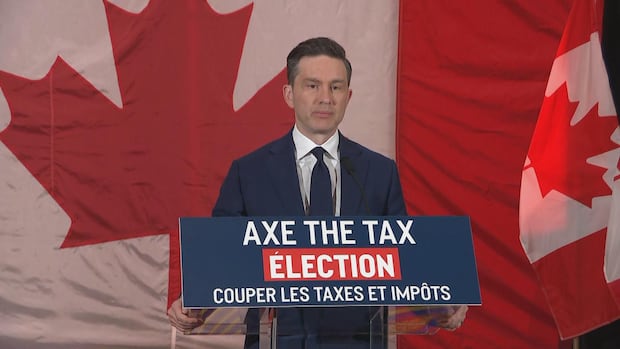

Pierre Poilievre, formidable Alberta challenger

On the other side of the aisle, Pierre Poilievre looms large.

Though he’s represented an Ottawa-area riding for 20 years, he was born in Calgary. At last summer’s Calgary Stampede, Poilievre leaned heavily into his local connections.

“Great to be home in my hometown,” he told a cheering crowd, before rhyming off the names of neighbourhoods where he grew up.

“I grew up in Shawnessy. Our first place was in Deer Run … and some of my best memories are from here, of course. I went to school — Janet Johnstone elementary school, went to [Henry] Wise Wood [High School] … grew up playing in Fish Creek Park.”

Poilievre’s Alberta roots give him an authenticity in the West that no other federal leader can match perhaps since Harper, who hailed from the same University of Calgary stream of young conservatives.

“We have a creative, dynamic, separate part of the country here that generates its own political leadership and its own political agendas,” said Brodie.

“And I don’t think it’s a surprise that the carbon tax was kind of crafted and pushed through by a government that was based in Ontario and Quebec.”

Carbon tax born in the West

The carbon tax started out as a trailblazing western policy, first introduced for heavy industry in Alberta in 2007 and for consumers in B.C. a year later. But it’s evolved from a symbol of environmental innovation into one of the most polarizing issues in Canadian politics.

For Poilievre, it’s the centrepiece of his demand for a “carbon tax election.”

Conservative Party Leader Pierre Poilievre says he believes the question of a carbon tax is important to Canadian voters because it could result in Canadian resource companies moving jobs and money south to the U.S. He added that massive tax cuts on energy are needed to bring production back to Canada.

Clark has already made her position clear. If she becomes the next Liberal leader and prime minister, she says she would scrap the tax.

It’s less clear what Carney and Freeland would do, but the tax itself has become a political minefield for candidates across jurisdictions.

“We’ve seen that in a lot of provinces where you’ve got leaders like [NDP] Naheed Nenshi here in Alberta, you’ve got Ontario political leaders, they’re all generally saying, ‘Yeah, we’re not going to do the carbon tax because it has become poison,'” said Corey Hogan, who headed the Alberta government’s communications and public engagement from 2016 to 2020.

Yet, as Hogan pointed out to West of Centre, the rhetoric often targets the consumer-facing aspect of the policy, leaving industrial carbon pricing — arguably the backbone of any serious emissions strategy — less scrutinized.

“When they’re saying carbon tax, they’re really meaning the consumer carbon tax — a big chunk of it is industrial pricing,” said Hogan, a former organizer for the Alberta Liberals.

The nuance is complicated for Liberal contenders. While industrial carbon pricing aligns with global norms, consumer carbon taxes have been weaponized politically, especially in regions like Alberta, where resistance runs deep.

“That issue could still unfold in a lot of weird ways, and it’s hard for me to imagine somebody like Mark Carney — were he to be [Liberal] leader — saying, ‘No, we don’t want an industrial price, either.’ In fact, Pierre Poilievre has been pretty quiet on that,” Hogan said.

Following Justin Trudeau’s announcement that he’ll be stepping down as prime minister once a new Liberal Party leader has been chosen, the discussion is now shifting to who might replace him. Catherine Cullen, host of CBC Radio’s The House, discusses some of the potential leadership candidates.

Regardless, Canadians are almost certainly headed to the polls with a consumer carbon tax policy still in effect, even if the next Liberal leader wants to undo the work. Moreover, figures like Carney, whose professional legacy is entwined with climate policies, would face significant challenges shaking off their association with carbon pricing initiatives.

“The first question in the first debate will be, ‘What is your position on carbon pricing?'” said former Liberal MP Martha Hall Findlay, now director of the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy. “How’s he going to answer that? So I don’t know how you can take it off the table.”

Appealing to western roots as a strategy

Whatever happens with the carbon tax, the West’s political clout is poised to grow, aided by structural quirks in Canadian politics.

This leadership races will operate on a points-based system, giving comparable weight to ridings with few members as to those with tens of thousands. The Conservatives have run leadership races with similar rules, in which the ridings with a thousand members in rural Alberta would have had the same voting clout as a less active riding in Montreal.

The system can disproportionately benefit candidates with connections to regions where their party is less active.

For the Liberal Party, this system offers opportunities for potential candidates like Clark, Carney and Freeland, should they play up their western roots to registered Liberals in the region.

“The three members in Fort McMurray — they sign up and are really going to turn the tide,” joked Brodie.

“I actually think in a funny way, Eastern Canada is at a bit of disadvantage,” Hogan said in response.

“If you’re looking at this and thinking, ‘Maybe I’d like to run, I’m Anita Anand, you know, maybe I’m not actually that enthusiastic about it because the amount of effort I’m going to need to do per point is going to be so much higher than somebody with legitimate ties to Western Canada.”

This dynamic sets up a fascinating test for candidates: how effectively they can translate personal connections and regional identity into political momentum in a national race.