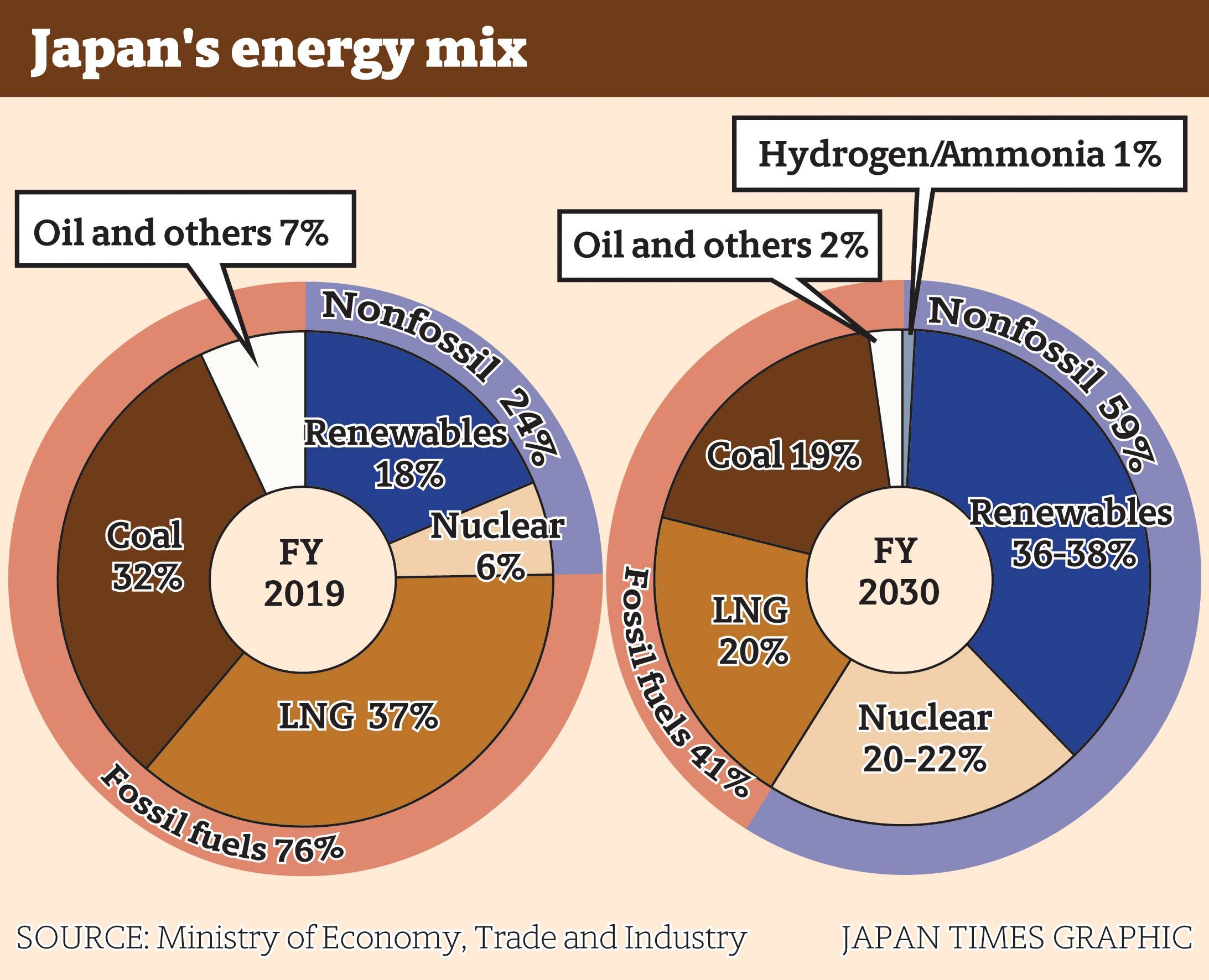

Japan aims to raise its share of nonfossil fuels for electricity generation, including renewables and nuclear power, to about 60% of total production by fiscal 2030 — 2.5 times the current level — the trade ministry’s draft basic energy policy showed Wednesday. But experts say the ambitious target may not be feasible.

The first revision of the energy policy in three years took into account the nation’s new target of a 46% cut in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 from fiscal 2013 levels that was announced in April, a sharp upgrade from the 26% cut that the world’s fifth-biggest emitter had pledged six years ago.

Renewable energy will account for 36% to 38% of total power production, up from 22% to 24% in the previous plan for 2030, while the share of nuclear power was kept at 20% to 22%. In fiscal 2019, renewables and nuclear made up 18% and 6% of total power generation, respectively.

If achieved, the total carbon dioxide emissions from the consumption of fossil fuels and power generation, which account for roughly 90% of the nation’s total, would fall by about a third from 2019 levels to about 680 million tons in 2030.

The new plan sets what experts say is a fairly high bar for renewables, with the share for solar, wind, geothermal, hydropower and biomass set to account for 15%, 6%, 1%, 10% and 5% in 2030, up from 6.7%, 0.7%, 0.3%, 7.7% and 2.6% in 2019.

The plan also projects that ammonia and hydrogen — the next-generation fuels that, unlike fuels such as oil and gas, do not produce carbon dioxide when burnt — will account for 1% of the total, though the cost will likely be much higher than that of natural gas. Production of ammonia and hydrogen by converting hydrocarbons generates carbon dioxide, although production of low-carbon forms of the fuels is increasing, with emissions captured via carbon-offset technology.

The doubling of solar power by 2030 may present one of the biggest hurdles, although it recently replaced nuclear as the cheapest source of power. Japan’s installed solar capacity per square kilometer on flat land is already the highest in the world, and the total installed capacity in Japan ranks the third highest.

The fact that only around 30% of land in Japan is flat, compared with 70% in Germany, will likely make it more difficult to raise the share of solar further, said Kouichi Iwama, professor of energy economics at Wako University.

“It will prove difficult practically and technically to construct a massive amount of solar power panels on the slopes of mountainous areas,” he said.

That leaves high hopes for offshore wind power, he said. Japan is targeting 10 gigawatts of offshore wind farms — equal to 10 nuclear reactors — by 2030, and 30 to 45 GW by fiscal 2040.

But there, again, Japan faces an uphill battle, as unlike Europe or Taiwan, which have an abundance of shallow coastal waters suitable for the installation of fixed-bottom wind turbines, Japan’s archipelago is surrounded by an ocean that tends to become abruptly deeper, meaning floating wind turbines are the optimal choice.

These kinds of turbines cost at least double that of their fixed-bottom alternatives, as in Japan they need to be built more strongly than the ones in Europe to withstand typhoons, earthquakes and tsunamis, energy experts say. The potential is huge as Japan has one of the world’s 10 largest exclusive economic zones, but according to industry sources they are still not economically feasible and there are only a limited number of projects that operate them commercially worldwide.

Iwama said that by taking advantage of fixed-bottom turbines, Japan may be able to achieve its 10 GW goal for offshore wind, but added that reaching the 45 GW goal by 2040 will be difficult, as it would require a significant reliance on floating turbines.

More than tripling the ratio of nuclear power to 20% to 22% in 2030 from 6% in 2019 also looks increasingly difficult, as that would assume that the operations of nearly 30 of Japan’s 33 commercial nuclear reactors would be resumed, he said. So far, only 10 reactors have restarted after meeting the strict nuclear regulations imposed after the Fukushima disaster in 2011.

According to Iwama, an absence of a concrete outlook on how to achieve the targets is a hallmark of the plan.

“Overall, the plan will be very difficult to achieve, as what they basically did is add up the numbers,” Iwama said.

Japan’s basic energy plan has traditionally set the share of nuclear power first and filled in the remainder, Iwama explained. But it has little chance of reaching the 20-22% goal for nuclear, as the new energy plan does not call for replacing old reactors with new ones or building new nuclear fleets. In addition, public opinion turned against the sector following the triple core meltdown at the Fukushima No. 1 power plant.

“The plan will be too difficult to attain, and it will have to be revised before long,” Iwama said.

The basic energy plan is set to be finalized by early next month and presented for public comment afterwards. After a formal approval by the Cabinet, it will be submitted to the U.N. COP26 meeting in Glasgow, Scotland, which will kick off on Oct. 31.

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever.

By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

SUBSCRIBE NOW