An idyllic community of soaring pines and seaside vistas feels like a one-of-a-kind nature preserve on the West Coast, filled with a particular subset of people who roam regularly across the Canada-U.S. border for love, livelihood and everyday life.

Now their migration patterns are disrupted. And after 16 months of restrictions on Canada-U.S. travel, residents of Point Roberts, Wash., sound like they’ve just about had it.

This place is a perfect spot to gauge the mood of people whose lives criss-cross the international border, thanks to a freak of geography that’s created an unusually high concentration of such people here.

Imagine a severed appendage of the United States, glued onto Canada’s hip — that’s this place. It’s a peninsula tip that would be a Vancouver suburb, were it not for an international border; instead, it’s a quiet American getaway.

Residents of this verdant maritime getaway have waited in vain, month, after month, for the end of border restrictions that have them imprisoned in paradise.

The place has no pharmacy. The closest one is across Roosevelt Road in British Columbia. Residents habitually cross the border to get medicine; to see doctors; even in some cases to see their spouses, as some couples keep homes apart for reasons of work or citizenship.

It’s such a tightly knit binational community that residents did something very unusual on the Fourth of July: dozens went to protest at the border, reached across it to hold hands with Canadian friends, and, on American Independence Day, joined in a rendition of O Canada.

The gas stations here list prices in metric litres for Canadians. Businesses rely on Canadians as the local population of 800 multiplies five times on summer weekends, when visitors drop in from Vancouver.

Those businesses are now being wiped out; some closed, and surviving ones say they’re barely clinging on, with revenues evaporating. The community’s main source of food — its only grocery store — is threatening to close.

Canadians’ summer homes lie empty; some are overrun with vines.

Caring for empty houses

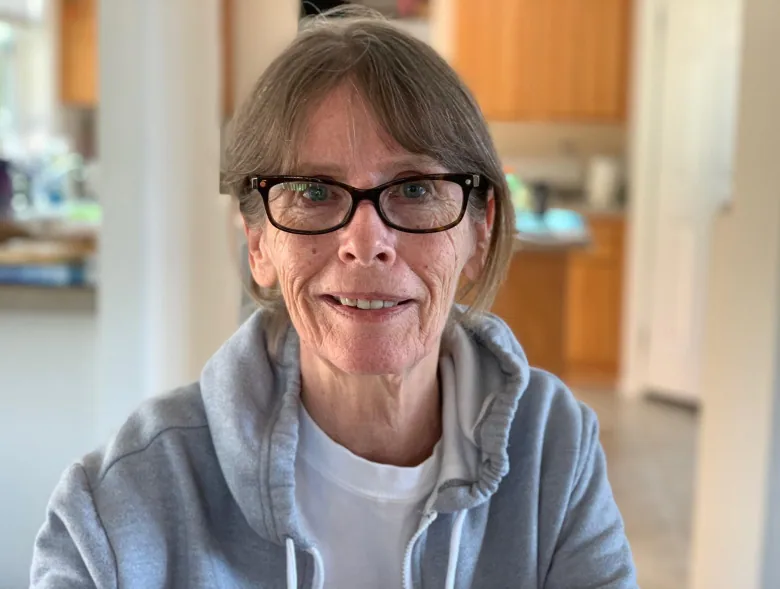

A pair of retired siblings are caring for these properties in Canadians’ absence. Jeanette Meursing and her sister are tending to 16 empty homes, spending more than 20 hours per week tidying lawns and gardens. They’re doing it for free in most cases, for friends.

“I honestly believe that these people, if I needed them, if I was sick or my husband was sick, and I needed help, they would be there to help me,” Meursing said in an interview.

“I don’t think there’s one that would say, ‘I don’t have time for you.'”

Her sister Diane Thomas says she’s found joy in the process, and shares a dark story to explain her perpetual sunny disposition.

She was shot in the face as a baby. A child had found an old, rusted .22-calibre rifle on a construction site in her native South Dakota.

It didn’t appear to work. When it accidentally, eventually, did go off, she was in its trajectory, and the bullet tore through her mouth into the back of her head.

She’s lived ever since with a bullet lodged precariously near her brainstem and says she reminds herself each day that her life is a miraculous gift.

So here she is now, at age 72, raking a yard surrounded by towering pines, expressing gratitude for being with her sister, safe, in a community that’s had few cases of COVID-19 and sky-high vaccination rates.

“We’re having fun,” Thomas said.

How a cartographic freak came into being

The border restrictions mean Canadians can’t drive down; Americans can’t drive up without an essential reason for travelling, and the definition of essential travel is subject to a border guard’s interpretation.

They can’t even access the rest of their own country without the twice-weekly foot ferry that drops them off, without a car, on the mainland of Washington state.

This cartographic aberration resulted from a U.S.-U.K. deal that drew the border through the 49th parallel, back in 1846 when the area had no permanent settlement.

Conversations with Canadian border guards have left some residents fuming about unclear and arbitrarily applied rules.

The locals even gossip about which border guards are the strictest.

Medical emergencies: At the guard’s discretion

Pamela Robertson recounts how guards brushed off her medical emergency.

When the pandemic struck, she had just completed part of a root canal with her dentist on the Canadian side. For months, the procedure languished unresolved. Then her gums got infected. Her face began to swell, with one cheek looking like a red billiard ball.

She was refused entry to Canada twice and asked a guard what it would take to get through.

“They looked me straight in the eye and said, ‘You have to be dying,'” she said in an interview. “I said, “I think I am dying. …

“They still wouldn’t allow me through.”

Finally, she got in on a third attempt; but she was ordered into a 14-day quarantine before she could see her dentist. She said had a fever and was dizzy by the final day. Eventually, she got surgery, and had to have two teeth removed.

“I lost two of my teeth,” she said, “because of … COVID and the stupid Canadian rules.”

Another local man was diagnosed with glaucoma.

Brian Calder, 80, says his Canadian doctor warned that he could lose vision in his left eye within six to 12 months without surgery.

By March, he was fully vaccinated and, on the day he was to have surgery, drove to the border with a medical note.

“And [the guard] says, ‘That’s not essential,'” Calder said. “And I say, ‘Well, what’s essential?’ [He replies]: ‘You’ve got to be dying.'”

He’s a dual Canadian-American citizen.

Calder says the guard informed him that he can’t, as a Canadian, be denied entry into Canada, but that if he tried driving to the doctor’s he would get a $3,000 fine, be forced into a hotel, and have to pay for quarantine for two weeks.

He’s finally managed to find a new doctor in the U.S., and get an appointment scheduled on the U.S. mainland, which residents can get to by car for medical emergencies if they drive straight through Canada without stopping.

“It’s not humane,” Calder says of the border situation. “It’s disciplinarian. It’s bullying.”

Fortunately, emergency services are allowed to cross. The local fire department relies on Canadians, who comprise two-thirds of its 48 firefighters.

The fire chief worries about this year’s brutal forest fire season.

He also worries about something more intangible: the frayed human connections. He says members of his community have missed the deaths and funerals of loved ones.

The toll on families

“I do believe we’ve lost a piece of humanity [during this pandemic] in the world as a whole,” said Christopher Carleton.

“The harshness and the lack of sympathy for people in particular situations — like a family death — it should never have happened.”

The chief performs different roles in the town, which has no mayor; in fact, it’s not even really a town but an unincorporated adjunct to Washington’s Whatcom County.

Carleton ran the local COVID vaccination drive that resulted in 85 percent of residents being fully vaccinated.

One fully vaccinated is desperate to see her family in Canada. Marlene Calder, Brian’s wife, has lost a precious year with her 94-year-old mother.

Her mom’s memory is fading. She wants to be able to drop in a couple of days a week, to help her mom and relieve the burden on her sisters.

“It’s heartbreaking,” she said. “It’s emotionally, mentally draining to not have contact with them. Not to see them.”

She’s among the minority who will be helped by new travel rules taking effect this week.

Canada says people already qualified to enter can now avoid quarantine if they’re fully vaccinated, and take tests; that will allow Calder, a dual citizen, to check in periodically on her mom.

Businesses bleeding money

Recreational travel remains forbidden and that means more pain for tourism-reliant businesses, which means most of them in Point Roberts.

One local merchant says he’s burning through his lifelong savings, having spent millions to build a wine bar, gas station, and UPS facility intended to supply Canadian visitors.

“I can barely make my utility bills,” Fred Pakzad, 76, said. He wishes government officials could visit this place and see the effect of prolonged shutdowns.

One restaurant owner has had a distinguished career, owning restaurants in New York and a Michelin-starred spot in France before settling here to be closer to family.

Now Tamra Hansen says the only reason she’s survived is she cooks herself without taking a salary, and is living off credit now with revenues down 90 per cent.

Hansen says she feels like this pandemic has revealed a lack of empathy for people, in different ways, in both the U.S. and Canada.

“I think it’s brought out the worst in both countries,” she said.

But she had reason to be happy on the Fourth of July weekend: Her mother had just arrived from Kelowna, B.C.

It took two days to make a trip that usually takes several hours. It required a car ride to Vancouver for a COVID-19 test, then another ride to a small regional airport, then a flight across the border to Bellingham, Wash. — flying is still allowed.

Then she took a ferry boat to Point Roberts. By the end of it all, she was sitting in her daughter’s cafe. Which, in normal times, is just an hour’s drive south of Vancouver.