It was the end of the world as they knew it and these women felt anything but fine.

The protesters had come from all over the Maritimes, wielding signs and body bags, wearing clown wigs and lab coats. On Feb. 29, 1984, a leap year, they stood chanting outside the gates of Camp Debert, home to Atlantic Canada’s only government fallout shelter designed to withstand a nuclear attack.

On that day, an estimated 329 people were expected to go inside the Debert bunker to participate in a dress rehearsal for nuclear war. The spots inside were reserved solely for high-ranking government and military officials and even some members of the media — nearly all of whom would be men.

And the women outside were incensed about who the government had been deemed worthy of protecting.

The women protesting that day, many of whom were linked to legendary Nova Scotia activist Muriel Duckworth and Canadian Voice of Women for Peace, first learned of the exercise from a small article published in The Chronicle Herald in July 1983.

They began planning a series of direct actions that would culminate on the day. The purpose was simple: to remind the people allowed inside the bunker that day of the cost of nuclear war.

“What happens to the families of those men who are going into the bunker?” asked Sue McManus, who was part of a group who had travelled from P.E.I. for the protest.

“How are they going to feel walking out of their homes, leaving their wives and their children behind, who are going to be detonated and incinerated, vaporized and radiated? It makes me angry. That’s why I’m here today.”

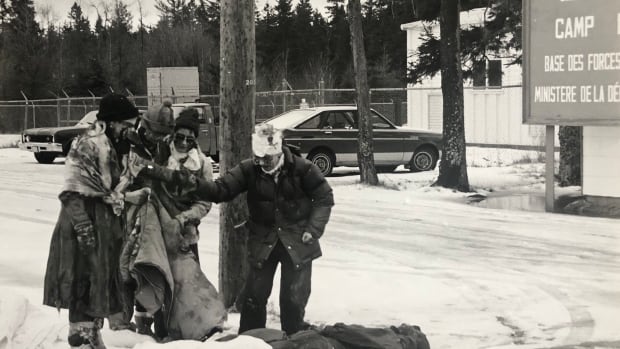

Many of the women dressed up as victims of radiation poisoning, their faces splotchy with burn marks, to illustrate the horrific aftermath of a nuclear attack. They carried the dead alongside with them in white body bags, making clear the toll an attack would take and the likelihood that few, if any, of the people outside would survive.

Five separate groups were participating, all with different but complementary ideas.

One group, composed solely of men, did all the cooking and handled the child care that day, while another, the group holding clipboards and wearing clown wigs and lab coats, posed as researchers proposing a different nuclear survival plan.

That morning, activist Pat Kipping appeared on CBC Radio’s Morningside as her alter ego from that group, Dr. M. Mutandis of the Debunk Debert Research Associates.

On national radio, she proposed an alternative plan to the government’s official nuclear war fallout strategy, which had been titled the Continuity of Government program. Debunk Debert’s strategy was less concerned with the survival of male-dominated government, than with the survival of the human race.

“We suggest that the 329 places that are now reserved for aging male, military and government and media people, be replaced by 329 women of childbearing age and that the bunker also include a sperm repository,” Kipping told host Peter Gzowski.

Her group wasn’t being picky about what men would be eligible to donate, either. They just had a few minor prerequisites.

“No man who has had any authority or power in the society today would be eligible,” she said. “We’re afraid that we just can’t have that material continuing.”

This counter-proposal was pure satire, of course. But to many listening, it sounded much better than the government’s official plan.

“It’s something that only men could come up with, right?” said Kipping, speaking nearly 40 years after the protest.

“Because the whole idea that you can continue government without another generation… they really weren’t thinking … and that really drove us crazy. But it just triggered so many different approaches and so many different groups of women to come.”

‘Announcer of doom’

One person who was originally set to be in the bunker that day was Don Connolly, the former longtime host of CBC Radio’s Information Morning Nova Scotia.

Inside the shelter was a replica CBC Radio studio, designed to make sure those in government would be able to get their message out to the unlucky masses not invited into the bunker that day.

Connolly was all set to become what he’d termed as the “announcer of doom.” Then a colleague, former CBC reporter Bette Cahill, called him one day and he had a change of heart.

“She said … ‘When the flag goes up, you’re going to leave Maureen and Molly and Kathleen at your place? You’re going to go to Debert, leave them, and say good luck with the nuclear attack?” Connnolly recalled.

“I said no, of course I’m not going to do that.”

Lessons to be learned from protest

The protest continues to live on through a documentary made by filmmaker Liz MacDougall, called Debert Bunker: By Invitation Only.

Looking at the state of the world today, Kipping is well aware that the fight for peace, equality, and a future for our planet is still ongoing.

She thinks that future activists would do well to look at the example set by Debunk Debert as they confront our present-day fears for the end of the world.

“I think it’s really important to challenge authority,” said Kipping. “I think creative activism is important. I think a sense of humour is really important, if only for the people who are doing the actions to keep their spirits up so they can keep being active.”

And though it took another decade, in the end, the activists involved with Debunk Debert got their wish.

In 1994, with the end of the Cold War, the federal government officially decommissioned Camp Debert. It was later sold and today hosts escape rooms and laser tag.