A video on the history of Urdu Bazaar, located opposite Gate number 1 of the historic Jama Masjid.

A video on the history of Urdu Bazaar, located opposite Gate number 1 of the historic Jama Masjid.

There was a time when Urdu did not have a religion. Back in 1975, we had a film called Jai Santoshi Maa, arguably the biggest hit among mythological movies. When the film released in Delhi, its posters were put up outside shops near Jama Masjid. The posters had the name of the film and the local cinema showing it scribbled in Urdu.

Why?

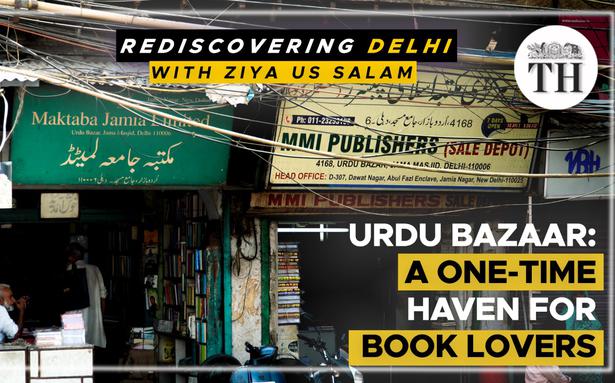

Because right there in all its glory was the grand old Urdu Bazaar opposite Gate number 1 of the historic Jama Masjid. It was a place where one could get the best of Urdu books, the works of fiction and non-fiction, constitutional law, Islamic law, the translation of the Quran and the Vedas and the Ramayana too.

Urdu poets and writers came down to Urdu Bazaar, some to discuss the latest in the world of Urdu literature, some to just flip through the books before buying. There were nearly 40 shops then, the most popular among them being Rashidia Book Depot, Qutub Khana Anjuman-e-Taraqqui Urdu, the Zulfiqar Book Depot and Maktaba Jamia.

Though all of them enjoyed the patronage of Urdu lovers who came from far and wide, some of them specialised in certain kinds of books. For instance, the books of Premchand and Kishan Chander could be had almost on demand at Maktaba Jamia whereas those on Islamic jurisprudence and commentaries on the Quran were more easily accessible at Qutub Khan Anjuman-e-Taraqqi Urdu.

Interestingly, many of the book stores made a little space for a calligrapher to put to pen select verses of the Quran. His art was expensive, but decorate the homes of the best poets and authors. Indeed, be the Islamic books of scholars like Maulana Maududi, Yusuf Ali, Pickthal or Maulana Wahiduddin or the best of Ismat Chughtai, Manto, Premchand or Sahir Ludhianvi and Kaifi Azmi, the Urdu Bazaar had it all.

Over a period of time, Urdu Bazaar has declined, The first blow came with the Partition when many of the well-read residents of the area shifted to Karachi or Lahore. Then came politics associated with the language as Urdu came to be considered the language of one community. Gradually, the book shops started closing down. Some gave way to shoe shops, some to those selling readymade garments.

Today, there are many eateries, offering piping hot Mughlai delicacies. Where one went for a kitab or a book, now one goes for biryani and kabab. No longer the language of the economy, Urdu is faced with an existential challenge. As are the Urdu bookshops.

Today, amidst endless tea and cola, kabab and biryani stalls, there are just a handful of shops, a calligrapher or two, and a few book lovers who still keep the flame burning.